Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), nicknamed the “Sphinx of Delft,” is one of the three masters of the Dutch Golden Age alongside Rembrandt and Frans Hals. This genre painter produced only 34 certain works in twenty years of career, working slowly for private patrons such as Pieter van Ruijven. Married to Catharina Bolnes, converted to Catholicism and father of eleven children, he experienced financial difficulties aggravated by the crisis of 1672 which caused his premature death in 1675. Having fallen into relative obscurity in the 18th century, he was rediscovered in 1866 by Théophile Thoré-Burger and achieved worldwide acclaim in the 20th century. His work consists mainly of intimate interior scenes characterized by a masterful use of light, the probable use of the camera obscura, a palette dominated by ultramarine blue and yellow, and masterpieces such as Girl with a Pearl Earring, The Milkmaid, and View of Delft.

Biography of Vermeer

Johannes Vermeer (baptized October 31, 1632, in Delft; buried December 15, 1675) stands as one of the three absolute masters of the Dutch Golden Age alongside Rembrandt and Frans Hals. Nicknamed the “Sphinx of Delft” by critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger in 1866, this Dutch painter specializing in genre painting produced a body of work of exceptional rarity—approximately 45 paintings at most over a twenty-year career—of which only 34 are currently attributed with certainty.

Vermeer’s father, Reynier Janszoon (initially called “Vos,” then “van der Meer”), practiced three occupations: silk weaver, innkeeper, and art dealer. He ran the inn “De Vliegende Vos” (The Flying Fox) before acquiring the “Mechelen” on Delft’s Markt in 1641. This atmosphere blending art commerce and precious fabrics would profoundly mark the child, as evidenced by the carpets and textiles omnipresent in his works.

Artistic Training: An Unsolved Mystery

Despite his admission to the Guild of Saint Luke on December 29, 1653, no document proves the identity of Vermeer’s master. Historians propose several hypotheses:

- Leonard Bramer (1596-1674), Delft painter close to the family

- Carel Fabritius (1622-1654), talented pupil of Rembrandt, arrived in Delft in 1650

- Abraham Bloemaert (1564-1661) in Utrecht, Catholic like his future in-laws

- Amsterdam painters such as Jacob van Loo or Erasmus Quellinus

The influence of the Utrecht Caravaggisti manifests in his early paintings, while his capacity for synthesis reveals rapid assimilation of multiple influences.

Marriage and Conversion

On April 5, 1653, Johannes married Catharina Bolnes, a wealthy Catholic from a prosperous brick merchant family in Gouda through her mother Maria Thins. This marriage initially met with resistance from his mother-in-law for financial and religious reasons. Vermeer’s probable conversion to Catholicism—a marginalized minority in the United Provinces—testifies to his profound integration into this milieu, as attested by three works with Catholic themes: Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (1655), Saint Praxedis (contested attribution, 1655), and The Allegory of Faith (circa 1670-1674).

The couple would have eleven children (four dying in infancy)—an exceptional number for seventeenth-century Holland—constituting a considerable burden that explains the painter’s progressive indebtedness.

Professional Career

Recognition in Delft

Vermeer was elected headman of the Guild of Saint Luke in 1662 at age 30 (the youngest since 1613), re-elected in 1663 and again in 1672. In May 1672, he appraised, alongside 34 other painters, a collection of twelve paintings in The Hague for the Elector of Brandenburg, concluding they were inauthentic.

Patronage and Production

Vermeer worked slowly (approximately three paintings per year), favoring private patrons rather than the open market:

- Pieter Claesz. van Ruijven, wealthy patrician tax collector, principal patron who acquired approximately 21 canvases

- Hendrick van Buyten, prosperous baker

This privileged relationship explains why his reputation, solidly established in Delft, scarcely extended beyond his city during his lifetime.

The Catastrophe of 1672 and Vermeer’s Death

The Rampjaar (Year of Disaster) of 1672 marked the beginning of the end. The double attack by Louis XIV (Franco-Dutch War) and the English fleet provoked a severe economic crisis. Maria Thins lost revenue from her farms flooded near Schoonhoven. The art market collapsed abruptly. In July 1675, Vermeer borrowed 1,000 florins in Amsterdam.

According to Catharina: “Not only had [my husband] been unable to sell his art, but moreover, to his great prejudice, the paintings of other masters with which he traded had remained on his hands. For this reason and because of the great expenses occasioned by the children, for which he no longer had personal means, he became so afflicted and weakened that he lost his health and died in the space of a day or a day and a half.”

Posthumous Bankruptcy

Catharina pawned two canvases to van Buyten (A Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid, A Woman Playing a Guitar) for a debt of 726 florins. She declared bankruptcy in April 1676. Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, microscopist, became curator of her estate on September 30, 1676.

Obscurity and Rediscovery

Eighteenth Century: Discreet Presence

Contrary to the legend of the “totally unknown genius,” Vermeer’s works continued to appear in sales. The Dissius sale of May 16, 1696, presented 21 Vermeers with laudatory comments. In 1719, The Milkmaid was called “the famous Milkmaid by Vermeer of Delft.” In 1822, the View of Delft was acquired by the Mauritshuis for 2,900 florins.

However, art historians accorded him a minor place. Gérard de Lairesse (1707) mentioned him “in the manner of old Mieris.” Arnold Houbraken (1718-1720) merely evoked his name without commentary.

1866: Thoré-Bürger and Vermeer’s Renaissance

Théophile Thoré-Bürger published three articles in the Gazette des beaux-arts (October-December 1866) that radically transformed perception of Vermeer. A radical democrat exiled by Napoleon III, he saw in Dutch genre scenes a “civil and intimate” painting opposed to subjects imposed by Church and monarchy. He nicknamed Vermeer “the Sphinx of Delft” in his writings.

Thoré-Bürger compiled the first inventory: 72 paintings (nearly half erroneously attributed). He praised “the quality of light” rendered “naturally” and the harmony of colors. Henry Havard (1888) authenticated 56 paintings; Cornelis Hofstede de Groot (1907) only 34.

Twentieth Century: Global Consecration

1921: Exhibition at the Jeu de Paume (Paris) with three masterpieces (View of Delft, Girl with a Pearl Earring, The Milkmaid). Marcel Proust discovered Jean-Louis Vaudoyer’s articles “The Mysterious Vermeer.”

1995: Joint retrospective at the National Gallery of Art (Washington) and Mauritshuis (The Hague)—20 paintings in Washington (325,000 visitors), 22 in The Hague.

2001: Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York) then National Gallery (London)—13 works by the master.

2017: “Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting” at the Louvre—12 paintings.

2023: “Vermeer” exhibition at the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam—at least 28 paintings.

Girl with a Pearl Earring, nicknamed “The Mona Lisa of the North,” and The Milkmaid now rank among the most famous paintings in the world.

The Oeuvre: Genres and Themes

Early Period: History Painting (1653-1656)

Vermeer began with large-format religious and mythological subjects: Diana and Her Companions (97.8 × 104.6 cm) and Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (160 × 142 cm), belonging to the major genre according to academic hierarchy.

Allegories

- The Art of Painting (circa 1666-1668): personal manifesto preserved until his death

- The Allegory of Faith (circa 1670-1674): probable Catholic commission

Landscapes

Two masterpieces taking Delft as subject:

- The Little Street (circa 1657-1658)

- View of Delft (circa 1660-1661), admired by Marcel Proust and his character Bergotte

Genre Scenes: Core of the Oeuvre

Twenty-six intimate interiors in small formats, representing bourgeois domestic life with an ambivalent moral dimension:

- Love theme: recurrence of letter, music, and wine motifs (dishonest seduction)

- Vanity theme: jewelry, pearl necklaces, heavy earrings

- Models of virtue: The Milkmaid, The Lacemaker

- Particularity: The Astronomer and The Geographer—sole representations of men without female company, perhaps Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (contested hypothesis)

Female Busts

Three major works:

- Girl with a Pearl Earring (circa 1665)

- Portrait of a Young Woman (1672-1675)

- Girl with the Red Hat (circa 1666-1667)

These “morsels of painting” capture an attitude caught in the moment rather than a precise identity.

Technique and Style

Camera Obscura

Hypothesis formulated in 1891 by Joseph Pennell, confirmed by several elements:

- Disproportion between foreground and background (Officer and Laughing Girl)

- Blur effects creating depth of field (The Milkmaid, The Lacemaker)

- Rigor of central perspective (pinhole marks at vanishing points)

- Bold foreshortening (arm in The Milkmaid, “bulbous” hand in The Art of Painting)

- Erasure of contours under light (Girl with a Pearl Earring)

- “Pointillist” technique depicting luminous halos or “circles of confusion”

Palette and Colors

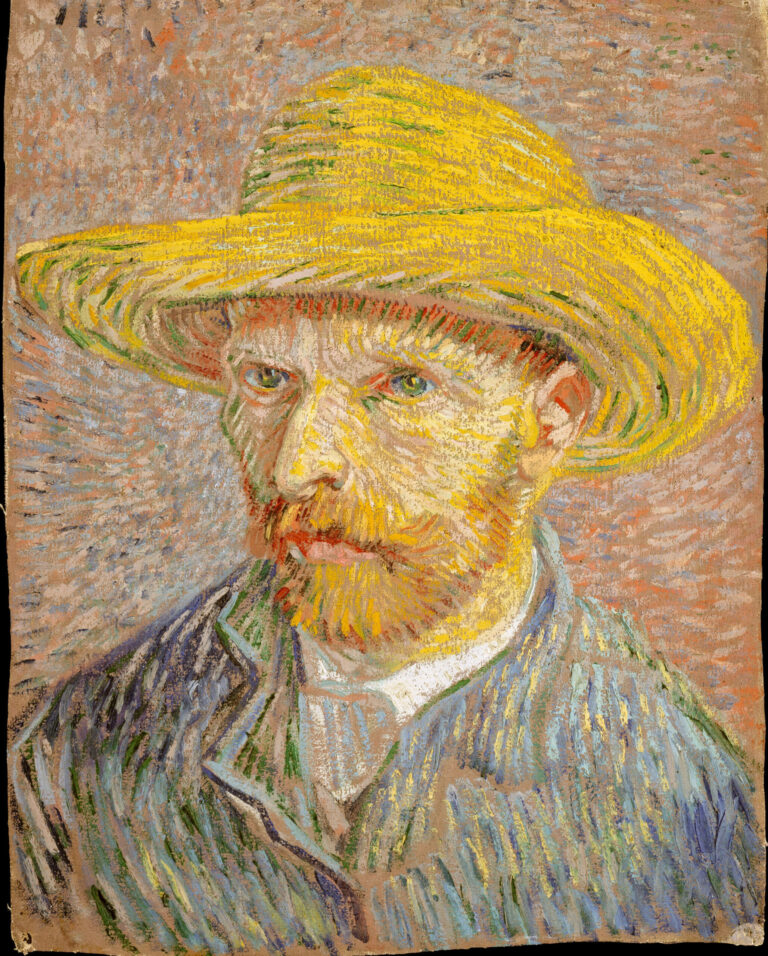

Vermeer used natural ultramarine (ground lapis lazuli) more than any seventeenth-century artist, including as underpainting to create subtle chromatic effects. Famous for his blue-yellow pairing (Girl with a Pearl Earring, Woman in Blue Reading a Letter) admired by Van Gogh.

His immoderate use of this costly pigment even after 1672 suggests a patron supplying his materials.

Recurring Elements

Objects: armchairs with lion-head finials (9 canvases), white or Delft blue faience pitcher, silver ewer (Maria Thins’s will), short ermine-trimmed yellow jacket

Spaces: black-and-white checkered pavement, corner pierced with shuttered windows, left-to-right lighting (except The Lacemaker)

Spectator/representation separation: curtains, tables, musical instruments in foreground (23 of 26 canvases)

Paintings-within-paintings: 18 works (6 landscapes, 4 religious paintings, 3 Cupids, Dirck van Baburen’s The Procuress owned by Maria Thins)

Geographic maps: copies of existing costly maps, signaling bourgeois milieu

Catalogue and Authenticity

Current Status

Of approximately 45 paintings executed during his career, 37 are preserved, of which 34 are attributed with certainty. Three remain contested:

- Saint Praxedis (1655): copy of Felice Ficherelli, ongoing debate

- Girl with the Red Hat (circa 1666-1667): on panel (not canvas), controversial authentication

- Young Woman Seated at a Virginal: largely subject to question

Girl with a Flute is now excluded from the corpus (eighteenth-century follower).

Dated Works

Only four dated paintings:

- Saint Praxedis (1655)

- The Procuress (1656)

- The Astronomer (1668)

- The Geographer (1669)

Signatures

Twenty-one signed works, but some signatures may be apocryphal, added later even on paintings by other masters.

Forgers: The Han van Meegeren Affair

The most famous forger, Han van Meegeren, produced several “Vermeers” including:

- Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus (1937): celebrated as a jewel by the master at a Rotterdam exhibition (1938)

- Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1943): acquired by Hermann Göring, causing van Meegeren’s downfall

Arrested in 1945 for selling Dutch cultural treasures to the Nazis, van Meegeren confessed to the forgery in his defense, shocking the art world.

Geographic Dispersion

No Vermeers remain in Delft today. The oeuvre is dispersed across the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, France, Austria, Ireland, and United States.

Major Public Collections

- Mauritshuis (The Hague): View of Delft, Girl with a Pearl Earring

- Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam): The Milkmaid, The Love Letter

- Louvre (Paris): The Lacemaker, The Astronomer

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York): A Maid Asleep, Woman with a Lute

- National Gallery of Art (Washington): Woman Holding a Balance, Young Woman with a Water Pitcher

Private Collections and Lost Works

- Lady Seated at a Virginal: acquired by Steve Wynn (2004), resold (2008)

- The Concert: stolen from Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (March 18, 1990), still missing

- Saint Praxedis: Barbara Piasecka Johnson collection

Bibliographic Sources

Reference Works

- John Michael Montias (1989): Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History—reference biography based on extensive archival research

- Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. (1995): Washington/The Hague exhibition catalogue—technical and chronological analysis

- Albert Blankert: Catalogue raisonné of works

- Daniel Arasse (2001): Stylistic and interpretive analyses

- Norbert Schneider: Studies on social and artistic context

Historical Sources

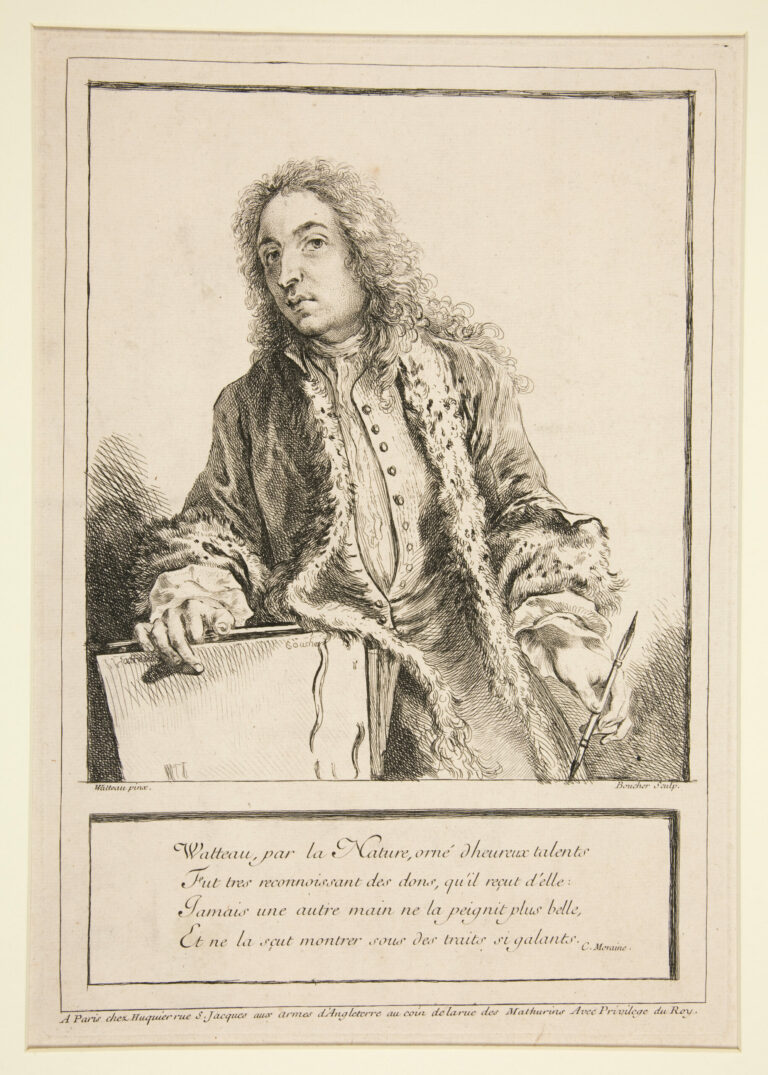

- Théophile Thoré-Bürger (1866): Foundational articles in Gazette des beaux-arts—rediscovery of the painter

- Balthasar de Monconys (1663): Account of visit to Delft mentioning price of 600 livres

- Arnold Bon (1654): Funeral oration after powder magazine explosion, designating Vermeer as Fabritius’s successor

- Gérard de Lairesse (1707): Het Groot schilderboeck

- Arnold Houbraken (1718-1720): The Great Theatre of Dutch Painters

Exhibition Catalogues

- Dissius Catalogue (May 16, 1696): Sale of 21 Vermeers with commentary

- Mauritshuis/Orangerie Exhibition (1966): “In Vermeer’s Light”

- Boijmans Van Beuningen Rotterdam Exhibition (1935): First retrospective

- Vermeer, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Exhibition (2023), by Gregor J.M. Weber, Pieter Roelofs et al. Designed by Irma Boom, Hannibal Books

Technical Studies

- Joseph Pennell (1891): First camera obscura hypothesis

- Mauritshuis Restorations (1996): Technical descriptions