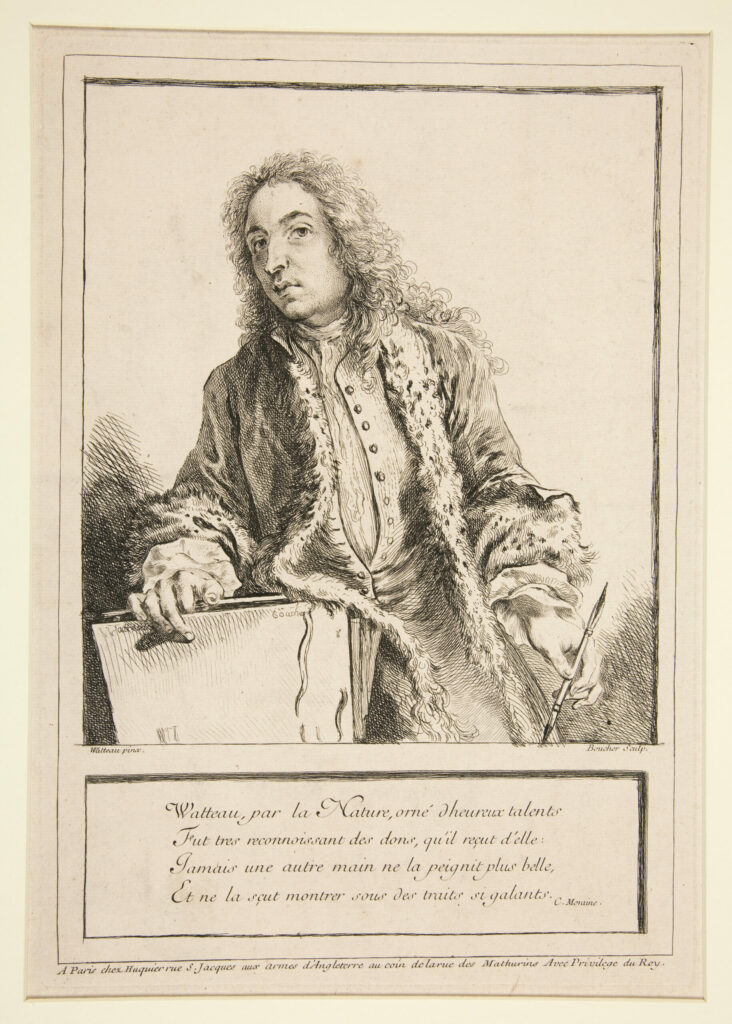

Jean-Antoine Watteau, born on October 10, 1684, in Valenciennes and who died prematurely on July 18, 1721, in Nogent-sur-Marne, remains one of the most fascinating figures in 18th-century French painting. Creator of the “fêtes galantes” genre and emblematic representative of the Rococo movement, he revolutionized the art of his time in just fifteen years of career.

Biography: Origins and Training

Born into a modest family, Watteau was the second son of Jean-Philippe Watteau, a master roofer and tile merchant, and Michelle Lardenois. His father, a quarrelsome and violent man, would deeply mark young Antoine’s sensitivity, perhaps contributing to his introverted character and fragile health. From the age of ten, his family encouraged his artistic vocation by placing him likely as an apprentice with Jacques-Albert Gérin, a renowned painter from Valenciennes.

Around 1702, the young man went to Paris and settled in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés district, the traditional refuge of northern artists. Without protection or resources, he survived initially by copying religious images and genre paintings for a manufacturer on the Pont Notre-Dame, earning barely “three livres per week and soup every day.” This difficult period nonetheless allowed him to forge crucial relationships with Nicolas Vleughels, Jean-Jacques Spoëde, and especially Claude Gillot.

Decisive Masters

Claude Gillot’s influence proved decisive in Watteau’s artistic formation. This painter, draftsman, and engraver of “original fantasy” introduced his student to the taste for theatrical scenes, gallant fantasies, and arabesques. Although their collaboration was brief due to their equally lively temperaments, Watteau would always maintain profound gratitude toward the one who allowed him to “completely find his way.” It was with Gillot that he developed his constant observation of surrounding realities and his taste for the spectacle of worldly life.

After his break with Gillot around 1707-1708, Watteau entered the workshop of decorator Claude Audran III, an experience that further enriched his training. Simultaneously, he benefited from the patronage of Pierre Crozat, an enlightened financier and collector, who invited him to reside in his Montmorency château and later in his private mansion on rue de Richelieu, alongside Charles de La Fosse.

Academic Recognition

In 1709, Watteau attempted the Prix de Rome but obtained only second place, preventing him from completing his training at the French Academy in Rome. This setback did not discourage him: he became a member of the Royal Academy in 1712. However, it wasn’t until 1717 that he presented his reception piece, the famous “Pilgrimage to Cythera,” a work that definitively established the fêtes galantes genre.

Watteau’s Art

Watteau participated in the artistic quarrel of his time between Ancients and Moderns, marking the triumph of color and the victory of the “Rubenists” over the “Poussinists.” Inspired by the commedia dell’arte, he frequently represented theater in his compositions, both through curtains and themes. His most celebrated works, notably “Pierrot” (formerly titled “Gilles”) and his two versions of the “Pilgrimage to Cythera,” testify to his singular genius.

“Gersaint’s Shopsign,” painted toward the end of 1720, constitutes his final masterpiece. Departing from his usual pastoral framework, this work places him in the heart of Paris, demonstrating his gratitude toward the merchant who provided him lodging.

Watteau and Music

Music occupies a central place in Watteau’s work, who was himself an amateur musician. “The Venetian Festivities” (circa 1717) shows him playing the musette de cour, while “The Charms of Life” (circa 1718) features three different string instruments. “The Perfect Chord” (1718) perfectly illustrates his ability to translate musical harmony into pictorial harmony, creating an atmosphere of intimacy and poetry.

Decline and Death

Despite the success of his works, highly sought after by European princes and private collectors, Watteau neglected his precarious health. In 1719, he left for London, perhaps to consult Dr. Richard Mead, but the London climate did not benefit him much. Upon returning to France, he spent his final months at the property of Philippe Le Fevre, a friend of Abbé Haranger. He died in Gersaint’s arms in 1721, probably from tuberculosis, at only 36 years of age.

Artistic Legacy

Watteau condensed the spirit of the Regency in his canvases, although he survived Louis XIV by only six years. His works are characterized by subtle melancholy, a sense of life’s futility, and a graceful lightness that transcends the simple frivolity of gallant festivities. This poetic ambiguity, which his followers like Nicolas Lancret and Jean-Baptiste Pater vainly attempted to reproduce, constitutes the very essence of his genius.

Posthumous Influence

Thanks to Jean Jullienne, a friend and collector who had his works engraved, Watteau gained considerable diffusion after his death. Although his Rococo painting disappeared with the French Revolution, he was rehabilitated from the 19th century onward. Turner paid homage to him in 1831, Baudelaire placed him among the great masters in “The Beacons,” Verlaine drew inspiration from him for his “Gallant Festivities,” and the Goncourt brothers saw in him “the great poet” of the 18th century.

In the 20th century, writers like Rilke, Claudel, Gracq, and Sollers continued to celebrate his work. Some critics even see in his style a precursor to Impressionism. Watteau thus created, according to art historian Michael Levey, “the concept of the individualist artist, loyal to himself, and to himself alone,” prefiguring the modern figure of the independent artist.

This biography reveals a creator whose brief existence profoundly marked art history, bequeathing to posterity a work of timeless poetry that continues to move and inspire.