Pierre-Auguste Renoir was born on February 25, 1841, in Limoges, France, to a family of modest artisans. His father, Léonard Renoir, was a tailor, and his mother, Marguerite Merlet, a seamstress. In 1844, the family relocated to Paris in search of better prospects.

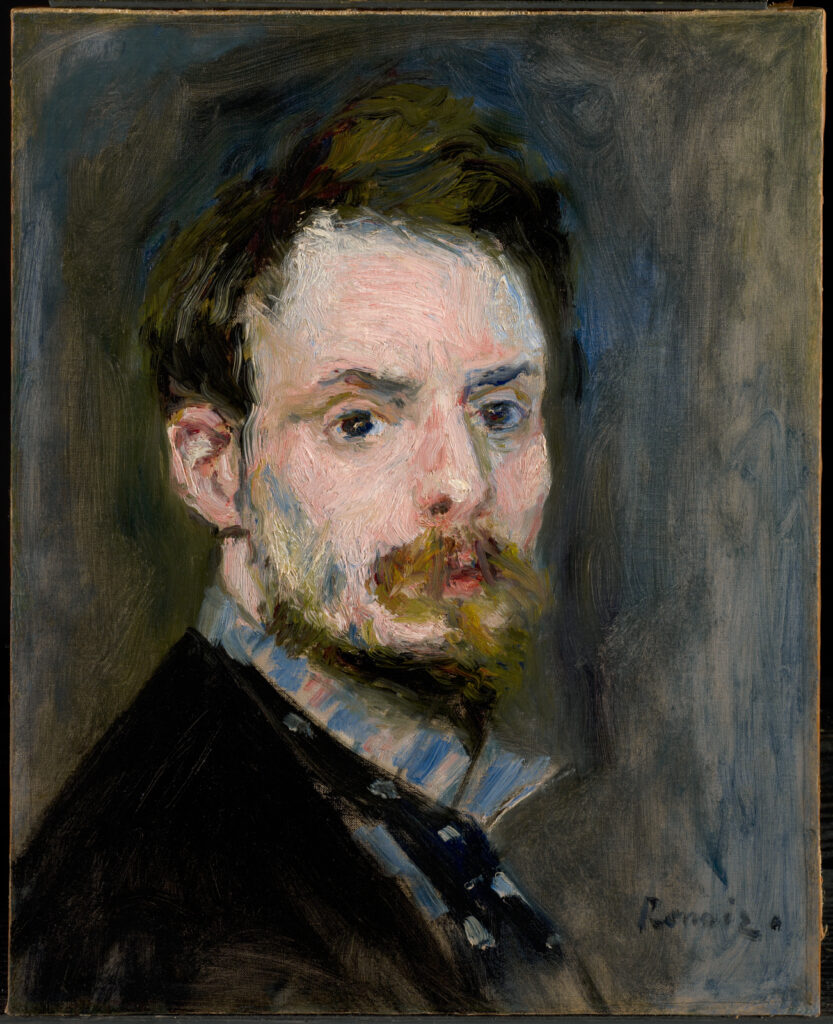

Auguste Renoir, a Biography

At the age of 13, Renoir began an apprenticeship at the Lévy Frères & Compagnie porcelain workshop, where he decorated pieces, already displaying a remarkable talent for painting. Concurrently, he attended evening classes at the School of Decorative Arts and Design, while also taking music lessons with Charles Gounod. In 1858, to support himself, he began painting fans and coloring coats of arms for his brother Henri, a heraldic engraver.

Early Painting Career (1862-1870)

In 1860, Renoir registered at the Louvre to copy classical works. The following year, he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, studying under Charles Gleyre, where he met Frédéric Bazille, Claude Monet, and Alfred Sisley. A strong friendship formed among these young artists, who often painted en plein air in the Forest of Fontainebleau.

After an unsuccessful attempt in 1863, his first painting, Esméralda, was accepted at the Salon of 1864. Despite its success, Renoir destroyed the work after the exhibition. That same year, he left the Beaux-Arts when Gleyre retired. During this period, his style was influenced by Ingres, Dehodencq, Gustave Courbet, and Eugène Delacroix.

In 1865, he formed a friendship with the painter Jules Le Cœur and met Lise Tréhot, who became his companion and favorite model for nearly eight years. Two children would be born from this relationship: Pierre in 1868 and Jeanne Marguerite in 1870.

The Impressionist Period (1869-1883)

Renoir’s stay with Monet at La Grenouillère on the island of Croissy-sur-Seine marked a decisive turning point in his career. He fully embraced painting outdoors, which transformed his palette and fragmented his brushwork. He learned to capture the effects of light and abandoned the use of black for shadows, thus inaugurating his Impressionist period.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, Renoir was mobilized in the cavalry. Upon returning to Paris, he was saddened to learn of the death of his friend Frédéric Bazille. His painting was then influenced by the realism of Édouard Manet, as evidenced in Still Life with Bouquet (1871).

In 1872, Lise Tréhot left him and married the architect Georges Brière de l’Isle. That same year, Renoir met the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, a relationship that would prove pivotal for his career. In the early 1870s, he frequently painted alongside Monet, producing images of the same subject and sometimes using members of the Monet family as models.

Regularly rejected by the official Salon, Renoir participated in the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874. The following year, to promote the group’s work, he organized an auction at the Hôtel Drouot with Durand-Ruel. Although controversial, this initiative attracted attention and enabled the group to gain supporters and patrons.

In Montmartre, where he rented a studio at Rue Cortot in 1876 (now the Montmartre Museum), Renoir created his masterpiece, Le Bal du moulin de la Galette (Dance at the Moulin de la Galette), in 1877. This ambitious canvas perfectly illustrates the artist’s style and research during this decade: fluid and colorful brushwork, colored shadows, textural effects, play of light filtering through foliage, and scenes of Parisian popular life.

From Impressionism to Classicism (1878-1890)

Facing financial difficulties and often unfavorable criticism, Renoir decided in the late 1870s to no longer exhibit with his Impressionist friends and returned to the official Salon, which he considered the only path to success.

He was supported by patrons, notably the Charpentier family, owners of a publishing house whose journal La Vie moderne contributed to his reputation. It was through commissions for prestigious portraits, such as Madame Charpentier and Her Children (1878), that he became known and received increasingly more commissions.

His relationships with influential collectors, such as Charles Deudon and Paul Bérard, allowed him to paint portraits of wealthy families, including the Bérard children and the daughters of banker Louis Cahen d’Anvers (Pink and Blue, 1881).

The turn toward classicism began as early as 1880 but crystallized during a stay in Italy in late 1881. Upon encountering Raphael’s works, Renoir felt he had reached the limits of Impressionism and now aspired to a more timeless art. He then entered the so-called “Ingres” or “Harsh” period, culminating in 1887 with The Large Bathers. Contours became more precise, drawing more rigorous, and colors cooler, provoking the indignation of critic Joris-Karl Huysmans, who exclaimed: “Well, well! Another one who has been taken in by Raphael’s bromide!”

On his return journey from Italy in early 1882, Renoir stopped at Cézanne’s home in L’Estaque. He also traveled twice to Algeria (1881 and 1883), seeking the dazzling light and exotic subjects made famous by Delacroix fifty years earlier.

In 1883, Renoir confided to Ambroise Vollard: “Around 1883, there was a kind of break in my work. I had gone as far as I could with Impressionism, and I reached the conclusion that I could neither paint nor draw. In a word, I had hit a dead end.”

In 1885, Renoir became father to a son named Pierre, born from his relationship with Aline Charigot, whom he would marry in 1890. The reception of The Large Bathers was highly unfavorable: the avant-garde felt he had lost his way, while academic circles did not embrace it either.

The “Pearly” Period and Recognition (1890-1903)

From 1890 to 1900, Renoir adopted a more fluid and colorful style, often described as “pearly.” The first work of this period, Young Girls at the Piano (1892), was acquired by the French state for the Luxembourg Museum, marking the beginning of his official recognition.

In 1894, Renoir became father to a second son, Jean, who would become a renowned filmmaker. Gabrielle Renard, a young cousin of Aline who cared for the children, became one of his favorite models and his muse. During this time, he took on his only student, Jeanne Baudot, daughter of his physician.

Since 1889, Renoir had been living in a pavilion nicknamed the “Château des Brouillards” on Rue Girardon in Paris. In 1896, he became a property owner for the first time by purchasing a house in Essoyes, Aline’s native village, which would become the family’s summer retreat until the painter’s death.

This decade was also one of consecration. His paintings sold well, particularly through art dealers Ambroise Vollard and Paul Durand-Ruel. Critics began to accept and appreciate his style, while official circles recognized him: he was offered the Legion of Honor, which he initially refused but later accepted in 1900.

In 1897, a severe bicycle accident near Essoyes, where he fractured his right arm, marked the beginning of health problems that would worsen later on. In 1899, he attended Alfred Sisley’s funeral and donated his painting The Sweeper for a sale organized to benefit the deceased painter’s children.

The Final Years in the South of France (1903-1919)

In 1903, due to his worsening health condition, Renoir settled with his family in Cagnes-sur-Mer, whose climate was meant to be more favorable to him. After residing in several homes in the old village, he acquired the Domaine des Collettes, on a hillside east of Cagnes, to save the olive trees he admired that were threatened with destruction.

The works of this period are primarily portraits, nudes, still lifes, and mythological scenes. His canvases are shimmering, his pictorial material more fluid, all in transparency. The round and sensual female bodies radiate life. However, deforming rheumatism progressively forced him, around 1905, to give up walking.

Despite these trials, Renoir was now a major figure in the Western art world. He exhibited throughout Europe and the United States and participated in the Autumn Salons in Paris. The material comfort he acquired did not cause him to lose his sense of reality or his taste for simple things.

From 1913 to 1918, in collaboration with Richard Guino, a young sculptor of Catalan origin introduced by Aristide Maillol and Ambroise Vollard, Renoir created a set of major sculptures: Venus Victrix, The Judgment of Paris, The Large Washerwoman, The Blacksmith. The attribution of these works would be the subject of a lengthy trial in the 1960s-1970s, resulting in the recognition of Richard Guino as co-author.

Aline died suddenly of a heart attack in June 1915. His sons Pierre and Jean were seriously wounded during World War I but survived. Jean took advantage of his demobilization to collect his father’s memories and thoughts.

Despite the illness that deformed his hands (rheumatoid arthritis), Renoir continued to paint until his death on December 3, 1919, at the Domaine des Collettes, from pneumonia. It is said that on his deathbed, he asked for a canvas and brushes to paint a bouquet of flowers, declaring as he handed back his brushes: “I think I’m beginning to understand something.”

Initially buried with his wife in the old cemetery of the Château de Nice, the couple was transferred in June 1922 to the cemetery of Essoyes, as they had wished.

Renoir’s Artistic Legacy

Renoir occupies a singular place in art history. Having abandoned Impressionist landscapes in favor of human representation, he placed joy at the heart of his canvases, earning him the nickname “painter of happiness.” His painting, which illustrates the consequences of progress on society and portrays a joyful daily life in settings that are alternately urban or bucolic, intimate or popular, is paradoxically considered today as the archetype of “petit-bourgeois good taste.”

This perception obscures the fact that this figurative painting, sometimes judged as mawkish, was rejected by the public and critics for more than twenty years. In 1876, critic Albert Wolf wrote in Le Figaro: “Try to explain to Mr. Renoir that a woman’s torso is not a mass of decomposing flesh with green, purplish patches that denote the state of complete putrefaction in a corpse!” That same year, artist Bertall added in Le Soir: “In bizarre frames, grotesque contortions, crashes of color without form and without harmony, without perspective and without drawing.”

Long perceived as unfinished, clumsy, or hasty by collectors of his time, Renoir’s work was later recognized as revolutionary for having broken with the conventions of official art. The turn he took around 1890, when he reconnected with his favorite masters (Fragonard, Raphael, Boucher), earned him accusations of betrayal from his former Impressionist companions.

Art history, however, considers that this later period, marked by a return to classicism, strongly inspired a young generation of artists, including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Maurice Denis, and Pierre Bonnard. Thus, despite controversies and fluctuations in his reputation, Renoir’s work remains one of the most emblematic and popular in modern art, testifying to a unique sensibility that transcends schools and artistic movements.

A prolific artist, Renoir estimated having created about four thousand paintings during his sixty-year career. This considerable body of work, dispersed in the world’s greatest museums and numerous private collections, continues to fascinate the public with its light, sensuality, and celebration of the beauty of the world.