Amedeo Clemente Modigliani (1884-1920), an Italian artist associated with the School of Paris, stands as a defining figure in early 20th-century art. Born in Livorno to a financially struggling but cultured bourgeois family, he developed an early artistic vocation supported by his mother, Eugénie Garsin, an independent-minded, intellectually vibrant woman.

Biography

Physically fragile from childhood, Modigliani grew between the conservative values of his paternal family and the more liberal, intellectual influence of his mother. His artistic training took him from Tuscany to Venice before his definitive installation in Paris in 1906, then the epicenter of European artistic avant-gardes.

History has long perpetuated the image of Modigliani as the accursed artist, consumed by alcohol, drugs, and tumultuous liaisons. This perception, intensified by the suicide of his last companion Jeanne Hébuterne the day after his death, has often eclipsed objective analysis of his work. Jeanne Modigliani, the couple’s daughter, was among the first to demonstrate that her father’s creative evolution was not defined by his tragic life but had instead evolved toward a form of serenity.

Formation and Influences (1884-1905)

Modigliani’s formative years began in his native city at the Livorno Academy of Fine Arts under Guglielmo Micheli, a painter trained by Giovanni Fattori of the Macchiaioli school. These artists, inspired by Corot and Courbet, had broken with academicism to prioritize painting from life and color over drawing. During this period, the young artist absorbed major artistic currents, developing a predilection for Tuscan art, Gothic and Renaissance Italian painting, and Pre-Raphaelitism.

A pivotal moment occurred in 1901 during a journey through southern Italy. In Naples, he discovered the archaeological museum, the ruins of Pompeii, and the sculptures of Tino di Camaino. It was likely here that his vocation as a sculptor emerged, well before his arrival in Paris.

Between 1902 and 1906, Modigliani continued his education in Florence and Venice. In Florence, he attended Fattori’s Free School of Nude and immersed himself in masterworks throughout the city’s museums and churches. In Venice, though rarely attending the Academy of Fine Arts, he enriched his artistic culture by discovering works by Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, Carpaccio, Tintoretto, Veronese, and Tiepolo.

His letters to his friend Oscar Ghiglia already reveal his elitist conception of art and his quest for an expressive line capable of translating the essence of beings and things beyond their material appearance. In Venice, he met Ardengo Soffici and Manuel Ortiz de Zárate, who introduced him to Impressionism, Cézanne, and Toulouse-Lautrec, while praising Paris as a crucible of freedom for audacious artists.

An Italian in Paris: Toward Sculpture (1906-1913)

Arriving in Paris in early 1906, Modigliani enrolled at the Académie Colarossi while assiduously frequenting the Louvre and galleries exhibiting Impressionists and their successors. He initially settled in Montmartre, moving between boardinghouses and furnished rooms, before alternating between the Left and Right Banks.

Modigliani quickly integrated into Parisian bohemian life. His natural elegance, culture, and charisma allowed him to form numerous relationships, particularly with Maurice Utrillo, Max Jacob, and later Chaïm Soutine. Although financially supported by his family, he lived in poverty which, combined with his consumption of alcohol and drugs, progressively deteriorated his health.

Between 1909 and 1914, Modigliani devoted himself primarily to sculpture without completely abandoning painting. He settled at the Cité Falguière, near Constantin Brâncuși, who encouraged him and convinced him that direct carving allowed one to better “feel” the material. He obtained limestone from former quarries or construction sites in Montparnasse and worked tirelessly on his sculpted heads, which he would sometimes arrange in the evening, adorned with candles, in a kind of primitive mise-en-scène.

His sculptural style drew from various sources: ancient and Renaissance statuary, African art, Oriental art, and contemporary works. In 1911, he exhibited several women’s heads in Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso’s studio, then at the 1912 Autumn Salon where he presented “Heads, Decorative Ensemble.” As for the caryatids, of which he left only one unfinished, he conceived them as “columns of tenderness” for a “Temple of Voluptuousness.”

Modigliani gradually abandoned sculpture from 1914 onward, as doctors had repeatedly advised against this practice due to his pulmonary problems. Other factors may have contributed to this renunciation: the physical strength required by direct carving, lack of space, cost of materials, and pressure from his dealer Paul Guillaume, as collectors preferred paintings.

The Painter’s Passions (1914-1920)

From 1914, Modigliani intensified his pictorial activity. Until his death in 1920, he produced over 350 paintings that began to sell, despite the slowdown caused by World War I. His work concentrated on caryatids, portraits, and nudes.

His life remained characterized by wandering, alcoholism, and drug addiction. In Montparnasse, he frequented La Rotonde and Chez Rosalie, known for its inexpensive Italian cuisine. Under the influence of alcohol, he could be exuberant, reciting poetry or engaging in altercations. During the August 1914 mobilization, his pulmonary problems prevented him from being drafted. Unlike other artists, his works contain no allusions to the war.

In 1914, Max Jacob introduced Modigliani to Paul Guillaume, a modern art enthusiast who exhibited him in his gallery and remained his principal buyer until 1916. In December of that year, Léopold Zborowski discovered Modigliani’s paintings and became not only his fervent admirer but also his faithful friend and dealer until the end. With his wife Anna (Hanka), they supported him to the best of their ability, offering him a daily allowance, materials, models, and the freedom to paint at their home.

Modigliani conceived the act of painting as an affective exchange with the model: his portraits trace the history of his friendships and loves. The twenty-five voluptuous nudes he painted until 1919 fed the public’s fantasies about a libertine Modigliani.

On December 3, 1917, his first and only solo exhibition during his lifetime took place at Berthe Weill’s gallery. Two female nudes in the window immediately provoked a scandal: the police commissioner ordered five works to be removed on the grounds that their pubic hair constituted an offense to public morality. This commercial fiasco nevertheless brought publicity to the painter, attracting the attention of collectors such as Jonas Netter, Francis Carco, and Roger Dutilleul.

Jeanne Hébuterne and the Final Years

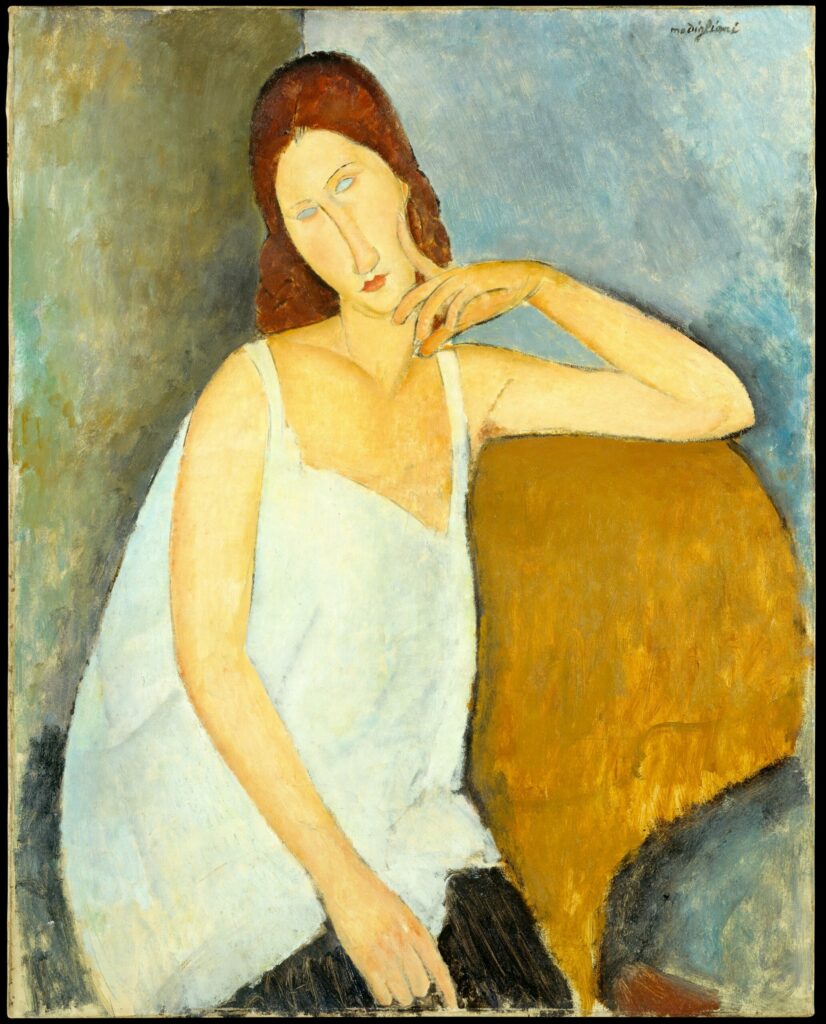

In February 1917, Modigliani fell in love with Jeanne Hébuterne, a 19-year-old student at the Académie Colarossi. Despite the opposition of her Catholic petite-bourgeois parents, she moved in with him in July 1917. Small, with auburn hair and a very pale complexion (earning her the nickname “Coconut”), Jeanne symbolized luminous grace and pure beauty for Modigliani. All their acquaintances remember her shy reserve and extreme gentleness.

Modigliani cherished Jeanne like no other woman before. He never depicted her nude but left twenty-five portraits of her which, like love letters, count among the most beautiful of his work.

In April 1918, facing rationing and bombardments in Paris, the couple departed for the French Riviera with the Zborowskis, Soutine, Foujita, and his companion. They first settled in Cagnes-sur-Mer, where Modigliani enjoyed a happy period, painting village children and adolescents. Then they moved to Nice due to lack of money. On November 29, 1918, their daughter Giovanna was born at Saint-Roch Hospital.

During these thirteen months spent in the southern sunshine, Modigliani worked joyfully. He tried landscape painting and created numerous portraits of children, adolescents, and people from all walks of life. Jeanne’s soothing presence generally enhanced his productivity.

Returning to Paris in May 1919, Modigliani began to gain recognition, but his health declined irreversibly. Jeanne, who joined him in June, was pregnant again, and he committed in writing to marry her. Zborowski negotiated his participation in the “Modern French Art – 1914-1919” exhibition in London, where the Italian was represented by fifty-nine works that achieved significant critical and public success.

Modigliani sensed his end approaching: pale, emaciated, suffering from nephritis, his cough was accompanied by blood. He stubbornly refused medical treatment despite his friends’ attempts. On January 22, 1920, Moïse Kisling and Manuel Ortiz de Zárate found him unconscious in his studio. Hospitalized urgently, he died two days later of tubercular meningitis. On the morning of January 25, Jeanne, then eight months pregnant, committed suicide by throwing herself from the fifth-floor window of her parents’ apartment.

The painter’s funeral gathered a thousand people on January 27, 1920. That same day, the Devambez gallery exhibited about twenty of his paintings: “Success and celebrity, which had eluded him during his lifetime, have never waned since.”

The Work and Its Visual Language

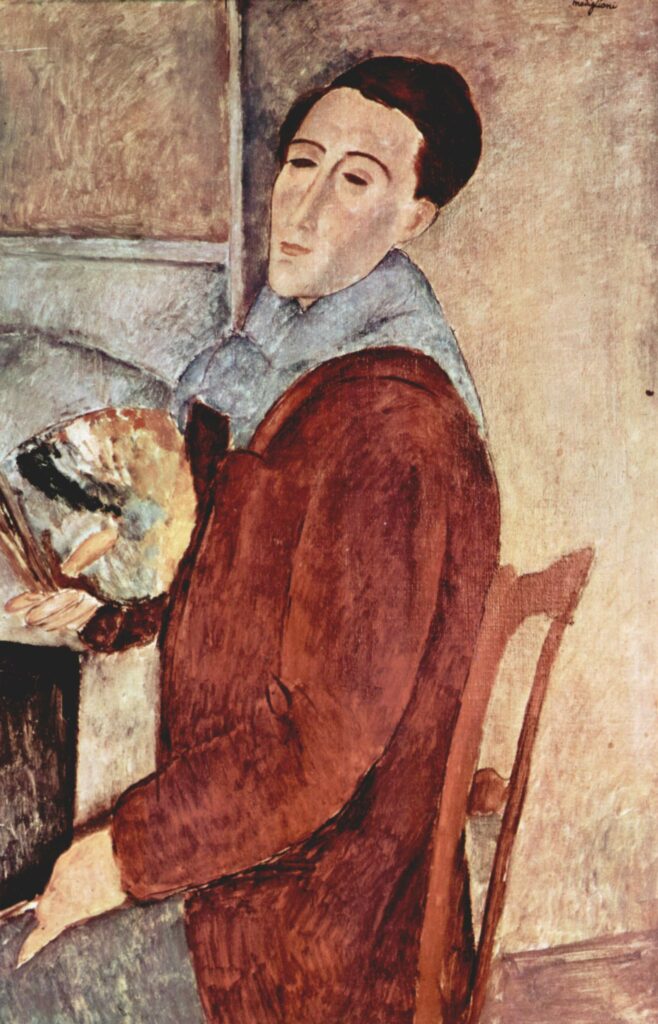

Modigliani’s oeuvre is characterized by a unique synthesis between tradition and modernity. His visual language developed independently of the avant-gardes, following a deeply personal approach.

His sculpture, inspired by both classical and primitive art, is distinguished by elongated and stylized forms. The approximately twenty-five stone heads he created demonstrate a search for formal purification and expression of essence beyond appearances.

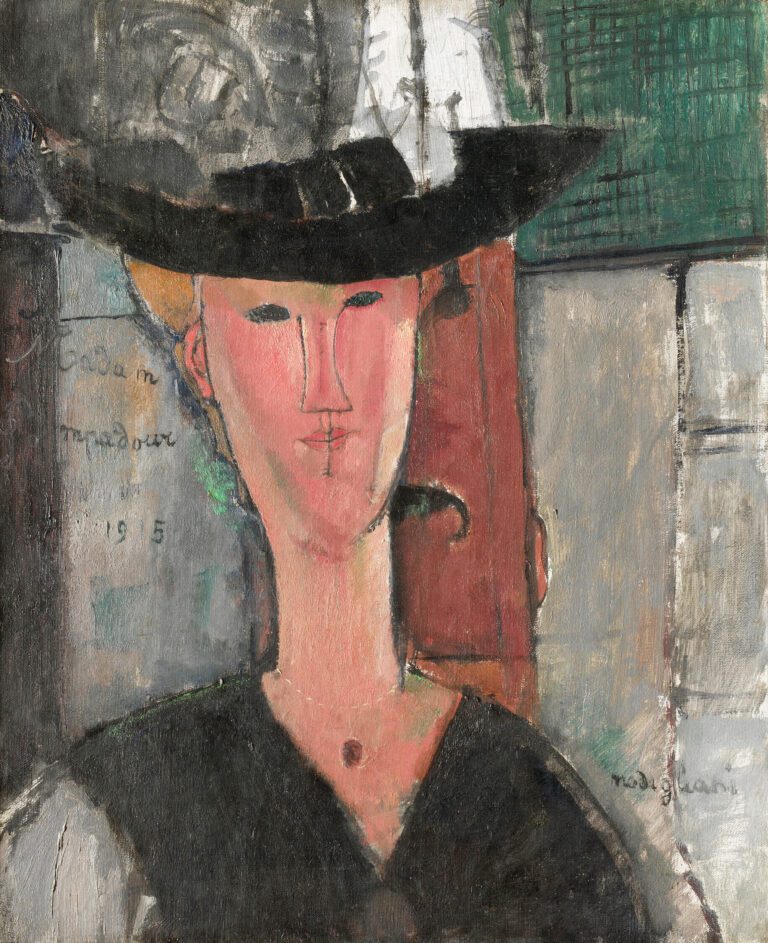

His painting, focused almost exclusively on the human figure, evolved toward increasing simplification and formal harmony. The portraits, characterized by oval faces, elongated necks, and often empty or asymmetrical eyes, reveal an acute sensitivity to the psychology of his models. The nudes, sensual and direct, inscribe themselves in a classical tradition while asserting an uncompromising modernity.

Modigliani’s palette, initially dark and influenced by Cézanne, gradually brightened to achieve subtle harmonies of blues, ochres, and reds. His ample and confident line delimits forms with simplified volumes that confer a monumental presence on his figures.

Legacy and Posterity

Modigliani occupies a singular place in 20th-century art history. Belonging to no particular movement, he developed an immediately recognizable style that reconciles the heritage of the Italian Renaissance with the formal innovations of his time.

While critics and academia were slow to recognize him as a major artist, considering that he had not played a decisive role in the evolution of the avant-gardes, his work has always found a profound resonance with the public. His lyrical and humanistic vision of the figure, his aesthetic of timeless elegance, have made him one of the most appreciated painters of the 20th century.

Beyond the myth of the accursed artist that long obscured an objective reading of his work, Modigliani’s oeuvre appears today as a constant quest for harmony and inner truth, a poignant testimony on the human condition that transcends the tragic circumstances of his life.

His influence can be perceived in numerous figurative artists of the 20th century, and the art market’s enthusiasm for his works has never diminished, making him one of the most highly valued artists in the world.

The singular and immediately identifiable beauty of his figures and the contained emotion they convey continue to profoundly touch viewers, testifying to the timeless power of a body of work that, beyond fashions and theories, speaks directly to our humanity.