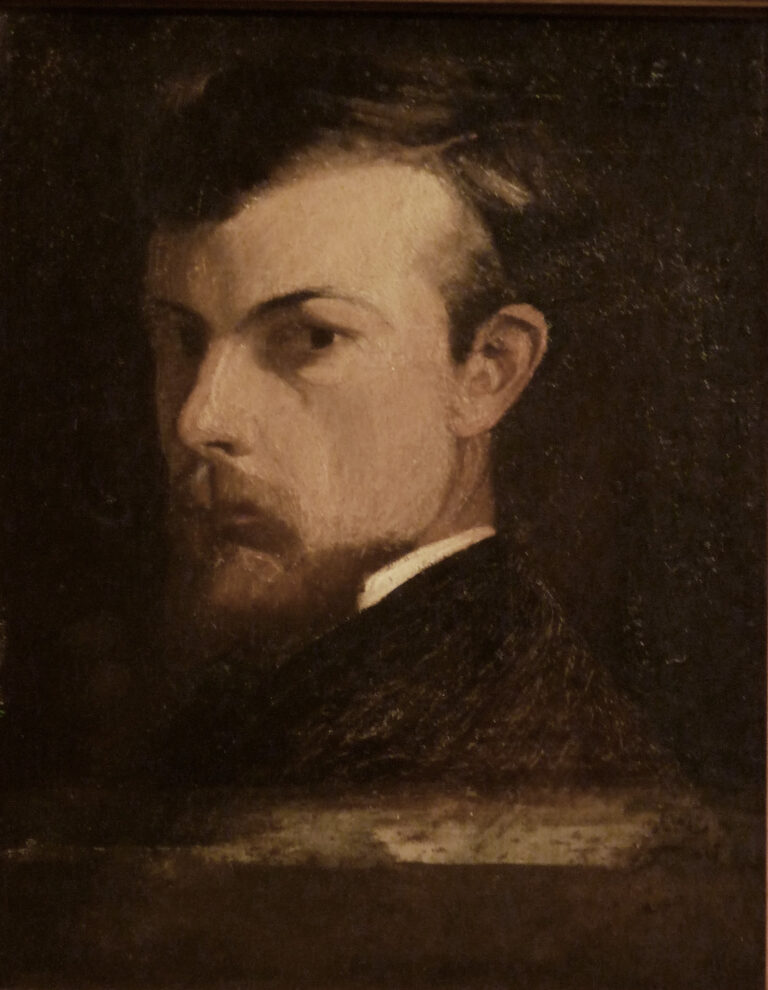

Gustave Caillebotte remains one of the fascinating figures of 19th-century French painting. Simultaneously a talented painter, generous patron, and visionary organizer, he played a decisive role in the development of modern art while creating a personal body of work of remarkable originality.

Gustave Caillebote’s biography

A Parisian Bourgeois Heir

Born on August 19, 1848, at 160 rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis in Paris, Gustave Caillebotte grew up in a prosperous bourgeois family. His father, Martial Caillebotte, built a considerable fortune in military textile commerce, notably as a supplier to Napoleon III’s armies. The family shop “Le Lit militaire” was located on rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis.

This financial comfort would determine Gustave’s entire artistic career. Upon his father’s death in December 1874, an inheritance of two million francs, supplemented by rental properties and various annuities, assured him complete independence, allowing him to paint according to his convictions without commercial constraints.

Academic Training and Artistic Awakening

After legal studies crowned by obtaining his law degree in July 1870, Caillebotte was mobilized in the National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War. This experience marked a rupture in his traditional bourgeois trajectory.

In 1871, he entered the studio of academic painter Léon Bonnat, where he met Jean Béraud. Although admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts in 1873 (46th in the competition), he remained only one year. During this period, he encountered the future pillars of Impressionism: Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, and Henri Rouart. These meetings would determine his artistic orientation.

The Emergence of an Original Talent

The “Floor Scrapers” Scandal

The year 1875 marked a decisive turning point. Caillebotte submitted his painting “The Floor Scrapers” to the official Salon, a work of striking realism depicting workers at their task. The jury categorically refused this canvas, judging the subject too trivial and “shocking in its extreme ordinariness.”

This work already revealed the singularity of Caillebotte’s approach. Unlike Courbet or Millet, he introduced no social or political message. His realism was purely aesthetic, founded on meticulous observation of gesture and contemporary environment. Paradoxically, this rejected painting is today one of the most celebrated works in the Musée d’Orsay.

A Revolutionary Technique

Caillebotte’s originality resided in his innovative pictorial technique. He developed audacious perspective effects, notably the “bird’s-eye view” which he invented in painting. His compositions compress distances, eliminate the traditional horizon, and create an unstable perception that anticipates certain modern art explorations.

His working method was scientifically rigorous: preparatory sketches, sometimes reference photographs, meticulous planning of vanishing lines, then methodical transfer from sketch to canvas, square by square. This methodical approach produced works of remarkable precision.

Patron of the Impressionists

A Providential Organizer and Financier

Rejected by the official Salon, Caillebotte naturally joined the nascent Impressionist group. From 1876, at only 27 years old, he participated in the second Impressionist exhibition at Durand-Ruel’s with several major canvases including “Young Man at His Window.”

His role quickly surpassed that of mere exhibitor. Thanks to his personal fortune and organizational skills, he became the movement’s true logistical pillar. He financed the third exhibition of 1877, coordinated participations, managed publicity, and enabled less fortunate artists to exhibit under favorable conditions.

In 1879, his commitment reached its peak: he presented more than twenty-five works at the fourth Impressionist exhibition, demonstrating his exceptional productivity and communicative enthusiasm.

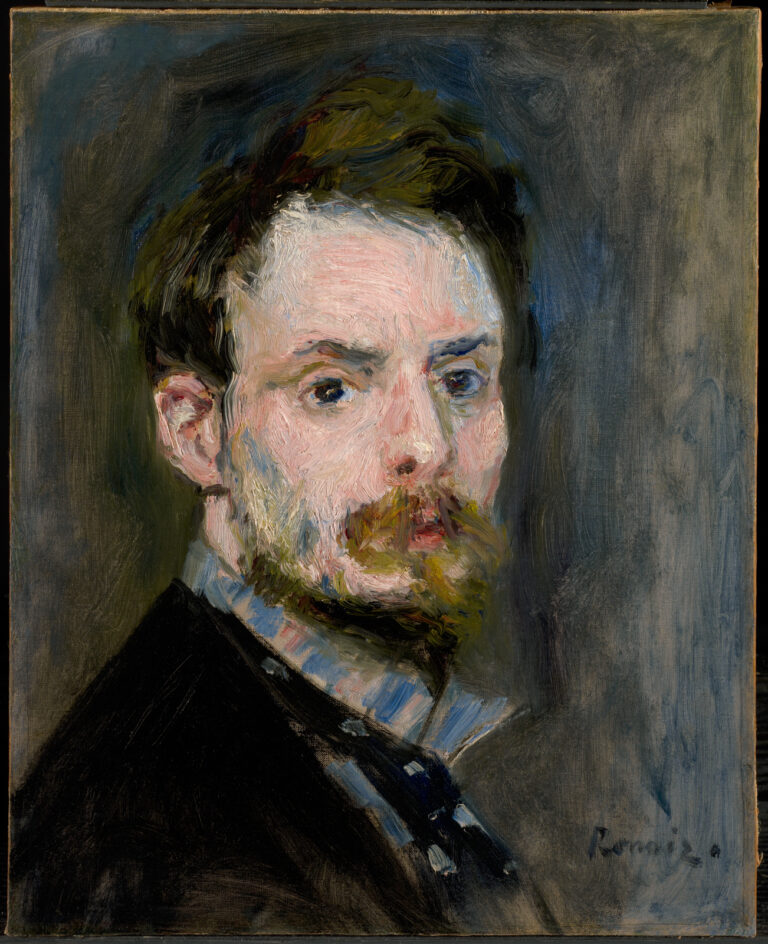

An Enlightened Collector

Parallel to his painting activity, Caillebotte assembled a remarkable collection of Impressionist works. He purchased canvases by Monet, Renoir, Degas, and Pissarro, financially supporting his colleagues while revealing sure taste for masterpieces in the making.

This collection, bequeathed to the French State by testament, would later form the core of national Impressionist collections. His generous gesture contributed decisively to the movement’s official recognition.

Personal Work: A Fresh Perspective on Modernity

Painter of Parisian Transformation

Caillebotte’s work uniquely witnesses Paris’s mutations under the Second Empire. His large urban canvases such as “Paris Street; Rainy Day” (1877) and “Le Pont de l’Europe” capture the spirit of the new Haussmannian Paris with remarkable psychological acuity.

According to art historian Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark, “among the Impressionists, Caillebotte becomes the most uncompromising interpreter of the transformed city.” He directs his gaze “toward the distant vanishing point of boulevards carved without remorse,” revealing the new geometry of the modern capital.

Exploring Modern Solitude

Beyond urbanism, Caillebotte excelled in capturing psychological states. His figures—whether moving through bourgeois salons, Paris streets, or even family intimacy—seem marked by a melancholy characteristic of the modern condition.

This psychological dimension clearly distinguishes his work from that of his Impressionist contemporaries, generally more concerned with light effects than emotional exploration.

Private Life and Passions

Companions and Family Environment

Caillebotte’s sentimental life remained relatively discrete. He maintained a lasting relationship with Anne-Marie Hagen, who posed for several of his paintings between 1876 and 1884, notably in the scandalous “Nude on a Sofa.” This relationship, disapproved by his family, ended around 1884.

He then settled with Charlotte Berthier, immortalized by Renoir in 1883, who shared his final years at Petit-Gennevilliers and inherited his property.

Petit-Gennevilliers: Refuge and Laboratory

From 1881, Caillebotte acquired a property at Petit-Gennevilliers, on the Seine’s banks. He had built there a millstone house, studio, boat hangar, and greenhouse. This place became his principal refuge after 1888, when his brother Martial married.

In this idyllic setting, he developed his passions for horticulture and boating. His gardens became a laboratory for his pictorial research on light and color, giving birth to works of exceptional luminosity.

Final Years and Legacy

Gradual Retreat from the Artistic Scene

After 1886, Caillebotte painted less and less, dedicating himself more to his gardens and summer regattas. This period paradoxically corresponds to some of his most accomplished works, notably his floral series of accomplished Impressionist technique.

He nevertheless maintained close ties with his artist friends. Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir were regular visitors to Petit-Gennevilliers, where passionate conversations about art, politics, and philosophy continued.

A Premature Death

On February 21, 1894, while painting a landscape in his garden, Caillebotte was struck down by cerebral congestion. He died at 45, at the height of his artistic maturity. His funeral at Notre-Dame-de-Lorette gathered a considerable crowd, witnessing the affection his numerous friends bore him.

Camille Pissarro summarized the general emotion: “We have just lost a sincere and devoted friend… Here is one we can mourn; he was good and generous and, which spoils nothing, a talented painter.”

Recognition and Posterity

A Belated Rediscovery

Paradoxically, Caillebotte’s pictorial talent was long eclipsed by his patron role. For decades, he was remembered only as the “enlightened collector” who enabled Impressionism’s emergence.

His rediscovery began in the United States in the 1970s, carried by American collectors sensitive to his urban realism. Edward Hopper would recognize him as a precursor of 20th-century American realist movement.

An Oeuvre of 475 Paintings

Caillebotte’s painted work comprises 475 paintings, a relatively modest number explained by his premature death and financial freedom that allowed him to paint without productivity constraints.

Approximately 70% of his works remain in his descendants’ collections, the others being principally conserved in American and French museums, notably the Musée d’Orsay which houses his most celebrated masterpieces.

Conclusion: An Unrecognized Master of Modernity

Gustave Caillebotte embodies a unique figure in 19th-century art. An original painter developing innovative pictorial language, generous patron enabling Impressionism’s flowering, efficient organizer and visionary collector, he marked his era through exceptional versatility.

His work, long underestimated, today reveals its full modernity. His perspective research, grasp of urban psychology, and treatment of modern solitude make him a precursor of contemporary artistic preoccupations.

The belated but now established recognition of Gustave Caillebotte confirms that he was far more than a simple wealthy amateur: a true artist whose contribution to modern art deserves full recognition and celebration.