Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), emblematic figure of French Romanticism and precursor of modern art, revolutionized painting through his innovative mastery of color and movement, embodying the fertile tension between classical tradition and modern sensibility. Trained at the École des Beaux-Arts under the determining influence of Géricault, he provoked resounding scandals from his early works with audacious paintings such as The Barque of Dante (1822), The Massacre at Chios (1824), and The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), before creating the universal icon of republican liberty with Liberty Leading the People (1830). His journey to Morocco in 1832 transformed his conception of light and color, nourishing a major Orientalist production, while his career gradually devoted itself to grand official decorative ensembles—Palais Bourbon, Senate, Louvre, and especially the Chapel of the Angels at Saint-Sulpice, his spiritual testament. A bachelor living between Parisian social circles and creative retreat at Champrosay, a visionary precursor in his relationship with nascent photography, he obtained belated official recognition with the Universal Exhibition of 1855 and his election to the Institute in 1857, before dying of tuberculosis in 1863, leaving a considerable influence on all the avant-gardes—Impressionists, Neo-Impressionists, Nabis—who saw in him the true founder of pictorial modernity.

Eugène Delacroix’s biography

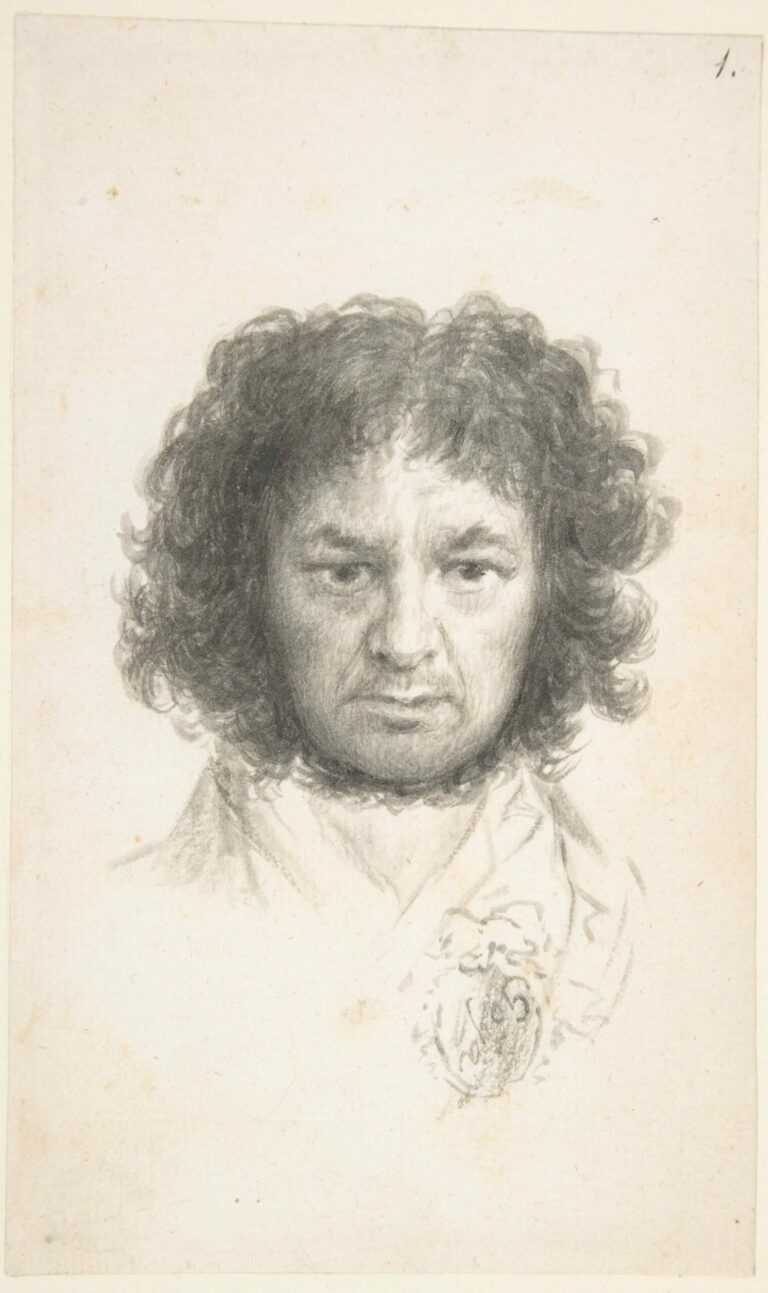

Eugène Delacroix was born on April 26, 1798, in Charenton-Saint-Maurice near Paris, into a distinguished family. He was the fourth child of Charles-François Delacroix (1741-1805), a lawyer who became a diplomat under the Convention and later a prefect during the Empire, and Victoire Œben (1758-1814), who descended from a renowned family of cabinetmakers. This dual heritage between politics and decorative arts perhaps foreshadowed the artist’s complex nature—both passionate and calculated, romantic and strategic..

The early deaths of his father when Eugène was only seven and his mother in 1814 profoundly marked his youth. He was taken in by his sister Henriette and her husband Raymond de Verninac. These parental losses, accompanied by financial difficulties, would influence his anxious relationship with money and his constant pursuit of official commissions throughout his career.

Delacroix’s education began at the Imperial Lycée (now Lycée Louis-le-Grand), where he received a solid classical education from 1806 to 1815. There, he formed lasting friendships with Jean-Baptiste Pierret, the Guillemardet brothers, and Achille Piron who would remain his confidants throughout his life.

In 1815, his uncle Henri-François Riesener arranged for him to enter the studio of painter Pierre-Narcisse Guérin. It was there that he met Théodore Géricault, seven years his senior, whose influence would be decisive. The following year, he continued his training at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. While academic teaching favored neoclassical drawing, Delacroix simultaneously developed his taste for color and movement.

A pivotal meeting with Charles-Raymond Soulier in 1816 introduced him to watercolor, an English technique that broadened his expressive palette. His journey to England in 1825 exposed him to Shakespeare’s theater, a major source of inspiration, and allowed him to discover the works of Constable and Lawrence that would influence his conception of color and portraiture.

Early Career and First Recognitions

Delacroix made a remarkable entrance onto the artistic scene with “The Barque of Dante” (1822), a painting inspired by Dante’s Inferno. Despite virulent criticism from defenders of neoclassicism, the work was acquired by the French State. The young journalist Adolphe Thiers already hailed “the future of a great painter,” while Gros described him as a “disciplined Rubens.”

In 1824, “Scenes from the Massacres at Chios” confirmed his talent and his commitment to the Greek cause. This work, inspired by current events—the massacre of the population of the island of Chios by the Turks in 1822—demonstrated his ability to transform a contemporary event into a striking romantic vision. Despite controversies, the painting received the second-class medal and was purchased by the State.

The exhibition of “The Death of Sardanapalus” at the Salon of 1827-1828 triggered general outrage. This painting with its flamboyant colors and bold composition was unanimously rejected by critics. Even his friends hesitated to defend it. This disastrous reception marked a break with the literary Romantic movement from which he already kept his distance.

The Revolution of 1830 and His Masterpiece

The July Revolution of 1830 inspired Delacroix’s most famous work: “Liberty Leading the People.” Presented at the Salon of 1831, this canvas depicts an allegory of Liberty as a young woman carrying the tricolor flag and leading the Parisian people over the barricades. Louis-Philippe’s government acquired it for 3,000 francs, but the canvas was quickly removed from the walls of the Luxembourg Museum, deemed too subversive.

Although he did not personally participate in the “Three Glorious Days,” Delacroix expressed in this painting his attachment to liberal ideals, without being a republican. He wrote to his brother that through this work, he wished to serve his country with his brushes since he had not fought for it. The painting would become, long after his death, an icon of the French Republic.

The Journey to Morocco: Revelation of a Luminous Orient

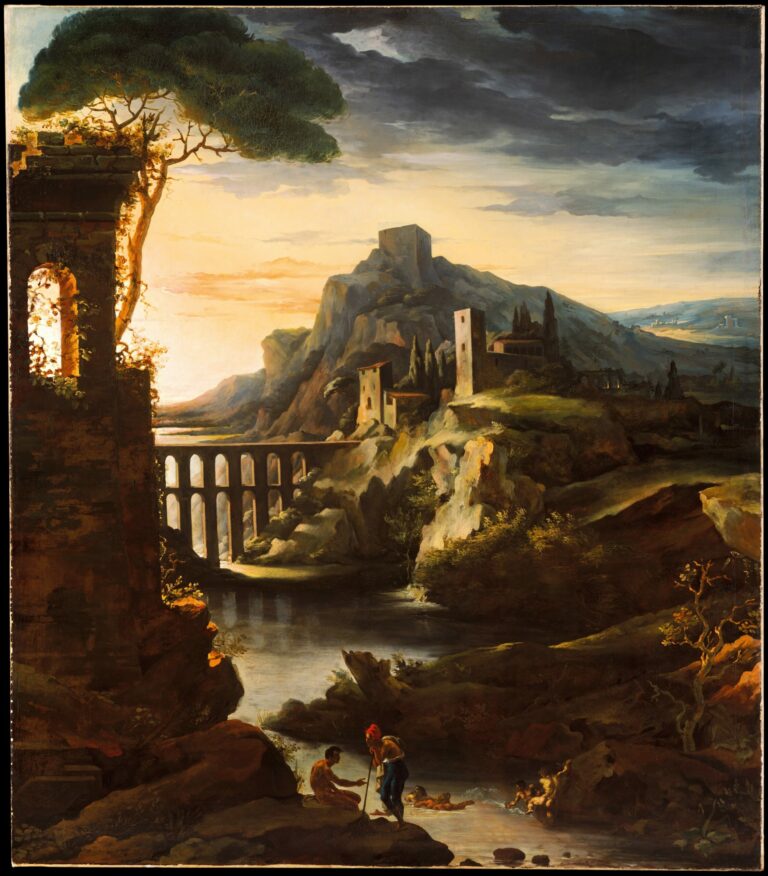

In January 1832, Delacroix accompanied, at his own expense, a diplomatic mission led by Count de Mornay to the Sultan of Morocco. This seven-month journey through Spain, Morocco, and Algeria radically transformed his artistic vision.

In his travel notebooks, he recorded with wonder his impressions of the landscapes, architecture, costumes, and customs of the local populations. He discovered in this “living Antiquity” a new light and a different approach to color. In Algiers, he had the rare opportunity to enter a harem, an experience that would inspire his famous painting “Women of Algiers in their Apartment” (1834).

This Oriental experience inspired more than eighty paintings created throughout his career, including “Jewish Wedding in Morocco” (1841), “The Sultan of Morocco” (1845), and numerous lion hunting scenes. The Orient became for him an inexhaustible source of picturesque and dramatic themes, but also a revelation about the harmony of colors and light.

Major Decorative Ensembles

From 1833, Delacroix’s career took a decisive turn with the first official commissions for monumental decorations. Thiers, then Minister of Public Works, entrusted him with the decoration of the Salon du Roi at the Palais Bourbon (now the National Assembly). This ambitious work, completed in 1838, includes a ceiling, friezes, and pilasters illustrating the vital forces of the State: Justice, Agriculture, Industry, Commerce, and War.

This first success was followed by other prestigious commissions:

- The Library of the Palais Bourbon (1838-1847), with five domes dedicated to Legislation, Theology, Poetry, Philosophy, and Sciences

- The Library of the Senate at the Luxembourg Palace (1840-1846), notably featuring the dome representing “The Meeting of Dante and Homer”

- The Apollo Gallery at the Louvre (1850), where he painted “Apollo Slaying the Python”

- The Chapel of Angels at Saint-Sulpice Church (1849-1861), his spiritual testament comprising “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel,” “Saint Michael Defeating the Dragon,” and “Heliodorus Driven from the Temple”

These decorative ensembles demonstrate his mastery of monumental composition and his ability to adapt his style to architectural constraints. They also reveal his profound classical culture and his faculty to renew traditional subjects through a personal and vibrant approach.

Private Life and Retreat to Champrosay

While Delacroix’s public life was marked by the social networking necessary to obtain commissions, his private life remained relatively discreet. A confirmed bachelor, he maintained several relationships with married women, including Eugénie Dalton, Alberthe de Rubempré, and Joséphine Forget.

From 1844, he rented a house in Champrosay, near the Sénart forest, where he regularly retreated to escape the Parisian bustle and tend to his fragile health. Accompanied by his housekeeper Jenny Le Guillou, who entered his service around 1835 and would become his faithful companion, he painted landscapes and still lifes in a more intimate atmosphere. He purchased this property in 1858 and spent his last summers there.

Delacroix and Photography

In the 1850s, Delacroix became interested in the nascent art of photography. A founding member of the Heliographic Society in 1851, he commissioned in 1854 a series of photographs of male and female nudes from photographer Eugène Durieu to use as working documents.

His relationship with this new medium was ambivalent: while he saw it as a valuable tool for anatomical study, he disputed that it could replace the art of painting. In his Journal, he noted: “I look with passion and without fatigue at these photographs of naked men, this admirable poem, this human body from which I learn to read.”

This pragmatic approach to photography illustrates his open-mindedness toward technical innovations while remaining faithful to his conception of art as personal expression rather than simple imitation of nature.

Late Recognition and Final Years

Official recognition came late to Delacroix. It was not until the Universal Exhibition of 1855 that he finally triumphed, with thirty-five paintings exhibited, a veritable retrospective of his career. He received the grand medal of honor and was made Commander of the Legion of Honor.

After seven unsuccessful candidacies, he was finally elected to the Institut de France on January 10, 1857, taking Paul Delaroche’s seat, despite Ingres’s opposition. This belated recognition did not bring him the satisfaction he had hoped for, as the Academy did not offer him the position of professor at the École des Beaux-Arts that he coveted.

His final years were darkened by illness. Suffering from tuberculosis, he gradually isolated himself, devoting himself entirely to completing the frescoes at Saint-Sulpice and writing his Journal. He died on August 13, 1863, in his apartment-studio on rue de Furstemberg in Paris, holding the hand of Jenny, his faithful housekeeper.

Legacy and Influence

Delacroix’s influence on subsequent generations is immense. As early as 1864, Henri Fantin-Latour paid tribute to him in a painting that gathered figures of the artistic avant-garde around his portrait. Manet, Cézanne, Degas, and the Impressionists claimed his heritage, particularly his color technique.

Paul Signac, in “From Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism” (1911), presented him as the precursor of divisionism. Van Gogh, fascinated by his work, copied several of his paintings. The Nabis, with Maurice Denis, saw in him a spiritual master. In the 20th century, Picasso himself drew inspiration from “Women of Algiers” for a series of variations.

His Journal, published posthumously, reveals a mind of great refinement, both theoretician and practitioner, analyzing with lucidity the problems of his art and his time. This exceptional document constitutes one of the most important artist’s reflections on creation.

Conclusion

A complex and contradictory figure, Delacroix embodies the fertile tension between tradition and innovation that characterizes 19th-century art. Classical in his culture and his attachment to the great masters, romantic in his sensitivity and expressiveness, he created a deeply personal body of work that transcends labels.

His mastery of color, his dramatic sense of composition, his ability to renew traditional subjects while drawing inspiration from current events make him a bridge between the Renaissance heritage and the advent of modernity. In this, Delacroix is not only the greatest French Romantic painter but one of the essential founders of modern art.

Bibliographical sources

- Delacroix, Eugène – Œuvres littéraires, E. Faure éd., 2 vol., G. Crès, Paris, 1923, rééd. Écrits sur l’art, Séguier, Paris, 1988

- Delacroix, Eugène – Journal, 1822-1863, A. Joubin éd., 3 vol., Plon, Paris, 1931-1932, rééd. revue par R. Labourdette, préface H. Damisch, Plon, Paris, 1980

- Delacroix, Eugène – Correspondance générale, A. Joubin éd., 5 vol., Plon, Paris, 1936-1938

- Delacroix, Eugène – Lettres intimes, A. Dupont éd., Gallimard, Paris, 1954, rééd. 1995

- Delacroix, Eugène – Dictionnaire des beaux-arts, A. Larue éd., Hermann, Paris, 1996

- Delacroix, Eugène – Souvenirs d’un voyage dans le Maroc, L. Beaumont-Maillet, S. Join-Lambert et B. Jobert éd., Gallimard, Paris, 1999

- Daguerre de Hureaux, Alain – Delacroix, Hazan, Paris, 1993

- Guégan, Stéphane – Delacroix, Flammarion, Paris, 1998

- Jobert, Barthélémy – Delacroix, Gallimard, Paris, 1997

- Johnson, Lee – The Paintings of Eugène Delacroix. A Critical Catalogue, 6 vol., Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1981-1989

- Rautmann, Peter – Delacroix, Citadelles-Mazenod, Paris, 1997

- Sérullaz, Maurice – Musée du Louvre. Cabinet des Dessins. Inventaire général des dessins. École française. Dessins d’Eugène Delacroix, 2 vol., Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris, 1984

- Eugène Delacroix, 1798-1863, catalogue d’exposition, Louvre, Paris, 1963

- Delacroix, les dernières années, catalogue d’exposition, Grand Palais, Paris, 1998

- Delacroix, le voyage au Maroc, catalogue d’exposition, Institut du monde arabe-Flammarion, Paris, 1994