Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606-1669), emblematic figure of the Dutch Golden Age, is universally recognized as one of the greatest masters in the history of Western painting, with nearly four hundred paintings, three hundred etchings, and an equal number of drawings. Trained in Leiden under Jacob van Swanenburgh and later in Amsterdam under Pieter Lastman, who introduced him to Caravaggesque chiaroscuro, he settled permanently in Amsterdam in 1631, where he achieved meteoric success through masterpieces such as The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632) and The Night Watch (1642), while marrying Saskia van Uylenburgh in 1634, of whom only their son Titus would survive. Following Saskia’s death in 1642, his personal life grew complicated with tumultuous relationships with Geertje Dircx and subsequently Hendrickje Stoffels, his companion until her death in 1663, while his style evolved toward a psychological depth and innovative pictorial materiality that distinguished him from the smooth classicism then in vogue. Declared insolvent in 1656 due to his lavish lifestyle and the decline in commissions, he nevertheless continued his work in poverty until his death in 1669, bequeathing final masterpieces such as The Jewish Bride and his ultimate self-portraits, which remain among the most moving in art history. His genius rests upon his revolutionary mastery of chiaroscuro, his tactile and rough approach to pictorial matter, his innovations in etching, and above all his profound humanism that transcends mere representation to capture the spiritual and emotional essence of the human condition, durably influencing artists from Goya to Van Gogh and Bacon.

Rembrandt’s Biography

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was born on July 15, 1606, in Leiden, in the United Provinces (present-day Netherlands), during the Dutch Golden Age. Born into a relatively prosperous family, he was the son of a miller, Harmen Gerritszoon van Rijn, and Neeltgen Willemsdochter van Zuytbrouck, a baker’s daughter. The ninth child of ten siblings, Rembrandt grew up in a modest but respected household.

His education began at the Latin School in Leiden, where he received classical training, before being enrolled at Leiden University around 1620. However, his artistic vocation manifested itself quickly, and he left the university to devote himself to painting. Around 1621-1622, he became an apprentice to the painter Jacob van Swanenburgh in Leiden, with whom he remained for approximately three years. This master, known for his scenes of hell and architectural views, taught him the fundamentals of painting.

In 1624, eager to refine his training, Rembrandt traveled to Amsterdam to study for six months under Pieter Lastman, a renowned artist known for his historical and biblical compositions. Lastman’s influence would be decisive in the development of Rembrandt’s style, particularly in his approach to biblical subjects and his dramatic use of light.

Early Success in Leiden (1625-1631)

Returning to Leiden in 1625, Rembrandt established his own studio. Unlike many artists of his time, he did not complete his training with a journey to Italy. This singularity would contribute to forging the originality of his style.

In Leiden, he worked closely with Jan Lievens, a painter of his age with whom he shared a studio for several years. During this period, he received his first important commissions and began to make a name for himself as a history painter and portraitist. He also developed an interest in “tronies,” those studies of faces and expressions that would become characteristic of his work.

His growing reputation attracted the attention of Constantijn Huygens, secretary to Prince Frederick Henry of Orange, who became one of his first important patrons. It was through Huygens’ mediation that Rembrandt received his first court commission in 1629: a series of paintings on the Passion of Christ.

It was also during this period that Rembrandt began to practice etching, a medium in which he would excel throughout his career and which would contribute greatly to spreading his fame throughout Europe.

Amsterdam Period and Zenith (1631-1642)

In 1631, attracted by the prospects offered by the commercial metropolis, Rembrandt permanently moved to Amsterdam. He entered into an association with the art dealer Hendrick van Uylenburgh, becoming his principal painter. This strategic alliance facilitated his integration into the commercial and social networks of the city.

In 1634, he married Saskia van Uylenburgh, Hendrick’s niece, who came from a Frisian patrician family. This advantageous union allowed him to access a higher social circle and obtain important portrait commissions. The couple settled in a spacious house on Breestraat (now Jodenbreestraat), in Amsterdam’s Jewish quarter, which also housed the artist’s studio.

The 1630s constituted the height of his public career. His reputation as a portraitist ensured him a prestigious clientele among the merchant bourgeoisie and intellectual elites of Amsterdam. In 1632, he painted “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp,” a group portrait commissioned by the surgeons’ guild that earned him immediate recognition.

During this period, he also built up an important collection of artworks, exotic objects, weapons, and costumes that served both as inspiration and as accessories for his compositions. His studio attracted numerous pupils, including Ferdinand Bol, Govert Flinck, and Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, who would help disseminate his style.

His masterpiece from this period is “The Night Watch” (actually titled “The Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch”), completed in 1642. This monumental canvas, commissioned by Captain Cocq’s militia company, broke with the conventions of group portraiture by creating a dynamic scene where light plays an essential structural role.

Personal Trials and Artistic Transformation (1642-1656)

The year 1642 marked a turning point in Rembrandt’s life. Saskia died of tuberculosis at the age of 29, shortly after giving birth to their son Titus, the only child of the couple to survive infancy (three other children having died at an early age). This loss inaugurated a difficult period both personally and professionally.

In 1649, Rembrandt began a relationship with Geertje Dircx, who was hired as a governess for his son. This liaison ended in a lawsuit when Geertje sued him for breach of promise of marriage. In 1647, he hired Hendrickje Stoffels as a domestic servant, who gradually became his companion until her death in 1663. Although they lived as husband and wife, they could not marry due to a clause in Saskia’s will that would have deprived Rembrandt of his inheritance in case of remarriage.

Artistically, this period coincided with a significant evolution. Official commissions became rarer, perhaps due to the evolution of his style, which was less conforming to the expectations of the bourgeois clientele, or due to scandals related to his private life. Rembrandt turned to more personal and introspective painting. His works gained in psychological depth and emotional intensity, as evidenced by his numerous self-portraits from this period.

His technique also underwent a transformation, gradually abandoning the polished finish of his early years for a freer and more expressive manner, where the pictorial matter became an expressive element in its own right.

Bankruptcy and Final Years (1656-1669)

Despite his artistic genius, Rembrandt experienced increasing financial difficulties. His lavish lifestyle, unfortunate investments in real estate, and perhaps a certain maladaptation to commercial realities led him to bankruptcy in 1656. His possessions, including his art collection and his house on Breestraat, were inventoried and sold at auction.

Forced to leave his home, he settled in a more modest neighborhood on the Rozengracht. To circumvent the restrictions related to his bankruptcy, he officially transferred his commercial activity to his son Titus and Hendrickje, who created a company to manage the sale of his works.

Paradoxically, these years of material adversity correspond to the peak of his artistic maturity. Freed from the constraints of commissions and market expectations, Rembrandt produced some of his most profound and innovative works. Paintings such as “The Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild” (1662) show that he had lost none of his mastery of group portraiture, while biblical compositions such as “The Return of the Prodigal Son” (circa 1668) reach an incomparable spiritual dimension.

The final years of the artist were marked by successive bereavements: Hendrickje died in 1663, probably from the plague, and Titus in 1668, a few months after his marriage, leaving a young pregnant wife. Rembrandt died on October 4, 1669, in Amsterdam and was buried in the Westerkerk. His last companion, Magdalena van Loo, and his posthumous granddaughter, Titia, would survive him.

Work and Artistic Style

Rembrandt’s work is characterized by its thematic and technical diversity. Throughout his career, he produced approximately 300 paintings, 300 prints, and 2,000 drawings. He addressed all the genres in vogue during his time: history painting, portraits, genre scenes, landscapes, and still lifes.

His most significant contribution to art history lies in his exceptional mastery of light. Initially inspired by Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro, he developed a personal and symbolic use of light that became a structuring element of his compositions and a vehicle for spiritual expression.

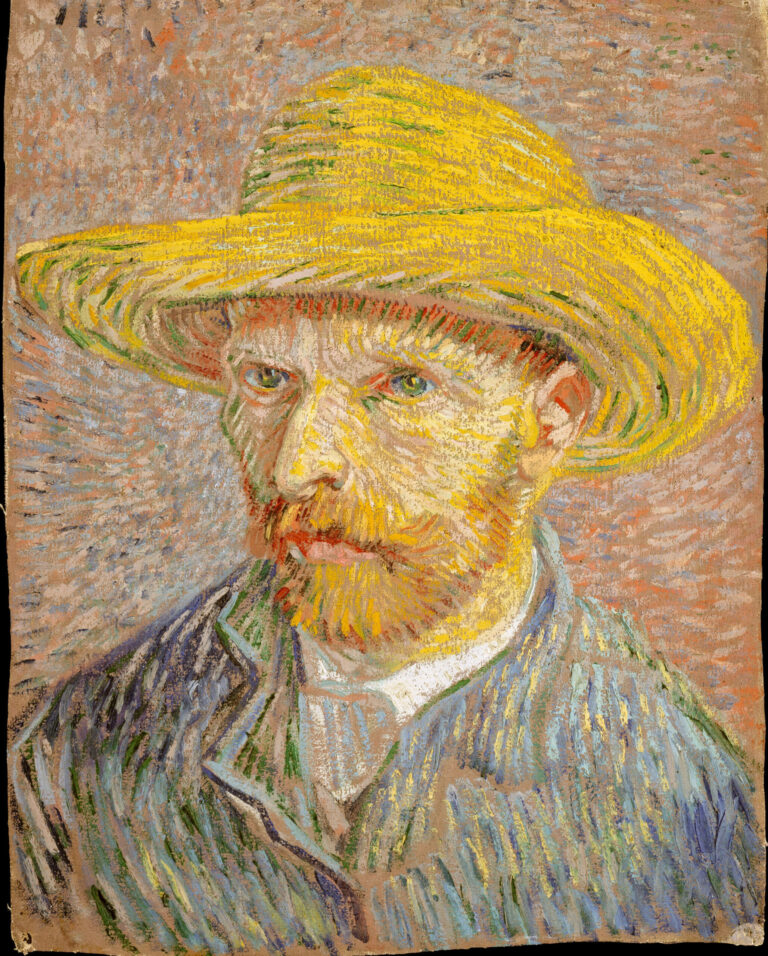

In his portraits, Rembrandt distinguished himself by his ability to capture the psychological truth of his subjects beyond social appearances. This search for authenticity culminated in his numerous self-portraits—nearly a hundred created throughout his life—which constitute an unprecedented visual chronicle of aging and introspection.

His style evolved markedly throughout his career. His early works are characterized by precise drawing, vivid colors, and careful execution. From the 1640s onward, his palette darkened, his touch became freer and more expressive, favoring suggestion over description. In his last works, he developed what is called his “late manner,” characterized by generous impasto, simplification of forms, and intensification of emotional expression.

As an etcher, Rembrandt also revolutionized etching techniques, exploiting all the expressive possibilities of the medium through his constant experimentation with inks, papers, and printing processes.

Legacy and Influence

Rembrandt’s influence on art history is considerable. During his lifetime, he trained numerous pupils who disseminated his style throughout the United Provinces. After his death, his reputation experienced fluctuations: relatively eclipsed in the 18th century by Rococo taste, his work was rediscovered and celebrated by Romanticism in the 19th century.

The Impressionists, and later the Expressionists, would recognize him as a precursor. Modern artists such as Van Gogh, Picasso, and Francis Bacon would also claim his heritage. His conception of art as an uncompromising exploration of the human condition and his technical audacity continue to inspire contemporary artists.

Today, Rembrandt is universally recognized as one of the greatest painters in the Western tradition. His works are preserved and exhibited in the world’s greatest museums, with particularly important collections at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the National Gallery in London.

Rembrandt’s work continues to question us about our own humanity, in its grandeur as well as its vulnerability. As art historian Ernst Gombrich wrote: “It is not technical refinement or stylistic innovation that makes Rembrandt an extraordinary artist, but his profound understanding of human experience.”

Bibliographical sources

- ALPERS, Svetlana, L’Art de dépeindre. La peinture hollandaise au XVIIe siècle, Paris,Gallimard, 1990.

- REMBRANDT RESEARCH PROJECT, A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, 6 vol., La Haye-Boston-Londres, Springer/Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project, 1982-2015.

- GERSAINT, Edme-François, Catalogue raisonné de toutes les pièces qui forment l’œuvre de Rembrandt, Paris, 1751.

- HOUBRAKEN, Arnold, Le Grand Théâtre des peintres néerlandais, Amsterdam, XVIIIe siècle.

- STARCKY, Emmanuel & SOKOLOVA, Irina (dir.), Rembrandt et son école, catalogue d’exposition, Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon/Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 2003.

- SCHWARTZ, Gary, Rembrandt, Paris, Flammarion, 2006.

- BOL, Laurens J., Rembrandt et ses élèves, trad. française, années 1960-1970.

- CLARK, Kenneth, Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance, Londres, John Murray, 1966 (édition anglaise) / An Introduction to Rembrandt, Londres, John Murray, 1978.

- GERSON, Horst, Rembrandt et son œuvre, Paris, Henri Veyrier/Le Livre Partout, 1968 [trad. française de Jean Carrère et Jeanine Carlander] (réédition 1980).

- BREDIUS, Abraham, Rembrandt. L’œuvre complet, Paris, Phaidon, années 1930-1940 (plusieurs éditions).

- HAAK, Bob, Rembrandt. Sa vie, son œuvre, son époque, trad. française, années 1960-1970.

- BONAFOUX, Pascal, Rembrandt, autoportrait, Genève, Skira, 1985 (réédition 1994).

- TÜMPEL, Christian & Astrid, Rembrandt, trad. française, années 1980-1990.

- WHITE, Christopher & BUVELOT, Quentin (dir.), Rembrandt par lui-même, cat. exp., Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, années 1990-2000.

- BOMFORD, David, BROWN, Christopher & ROY, Ashok, Art in the Making: Rembrandt, Londres, National Gallery, trad. française, années 1980-1990.

Rembrandt’s artworks and biography

- Rembrandt: The Standard Bearer

- Rembrandt van Rijn: The Abduction of Europa

- Rembrandt: Portrait of a Woman, probably Maria Trip

- Rembrandt: Man in a Turban

- Rembrandt: “Tronie” of a Man in a Feathered Beret

- Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of Oopjen Coppit

- Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of Marten Soolmans

- Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), Master of Light and the Human Soul

- Rembrandt: Aristotle with a Bust of Homer

- Rembrandt: Portrait of the Artist in Oriental Costume