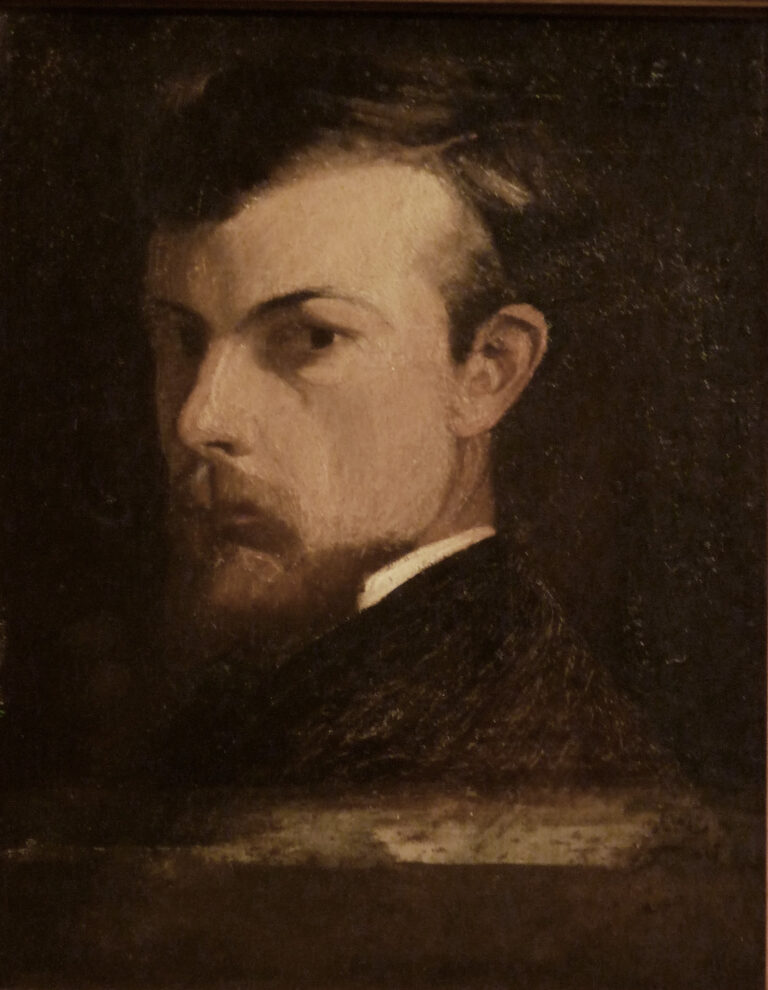

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, born March 30, 1746, in Fuendetodos near Zaragoza, and died April 16, 1828, in Bordeaux, stands as one of the most revolutionary figures in Western art. This Spanish painter and printmaker of extraordinary modernity introduced several stylistic ruptures that initiated Romanticism and heralded the beginning of contemporary painting.

Goya’s biography

Goya was born into a family of intermediate social standing. His father José was a master gilder, while his mother Engracia Lucientes descended from a family of hidalgos. This social position would enable him to navigate easily between different classes of Spanish society.

At thirteen, he entered José Luzán’s drawing academy in Zaragoza somewhat late for the period, studying there until 1763 in a traditional baroque style. Unstimulated by these studies, young Goya forged a reputation as a brawler and seducer in the conservative Spain of the Inquisition era.

After failing twice at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando competitions (1763 and 1766), Goya departed for Italy around 1770 at his own expense. In Rome, Bologna, and Venice, he discovered works by Raphael, Veronese, Rubens, and the baroque fresco painters. This journey marked a turning point: he gradually abandoned the dark chromatism of late baroque to adopt a more refined palette with pastel tones, influenced by the emerging neoclassical aesthetic.

Returning to Zaragoza in 1771, he received his first major commission: decorating the vault of a chapel in the Basilica del Pilar. The success of this fresco, The Adoration of the Name of God (1772), earned him the admiration of Francisco Bayeu, who granted him his sister Josefa’s hand in marriage in 1773.

The Madrid Ascension (1775-1792)

In 1775, through his brother-in-law Francisco Bayeu’s influence, Goya was appointed by Anton Raphael Mengs to court to work as a painter of cartoons for the Royal Tapestry Factory. This activity, which he would pursue intermittently for twelve years, allowed him access to aristocratic circles and the development of his personal style.

His cartoons rapidly evolved from works under tutelage to original creations. In series such as The Parasol (1777) or Blind Man’s Buff (1789), he captured the spirit of Madrid “majismo”—the aristocratic fashion of adopting the colorful costumes of the popular classes. These works demonstrate his growing mastery of realism and his ability to capture the customs of his era.

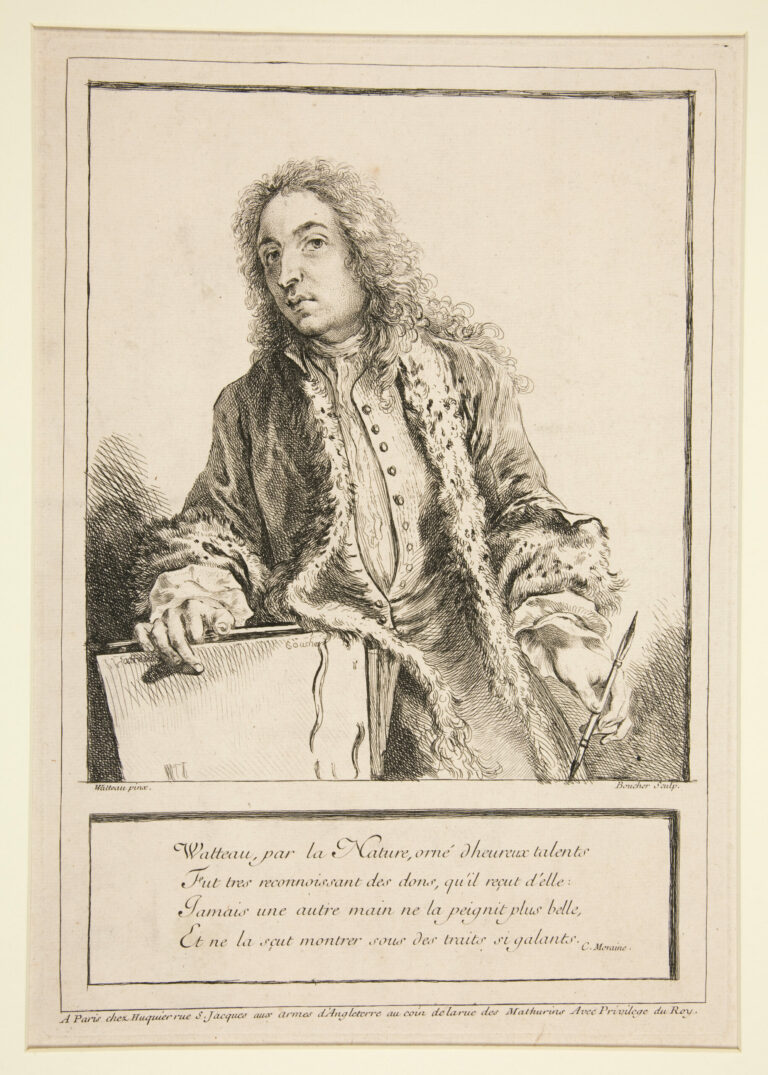

Simultaneously, Goya became a sought-after portraitist among high society. Influenced by Velázquez, whom he studied systematically and whose works he engraved in 1778, he developed an impressionist technique avant la lettre, playing with light effects and color touches to render textile textures and the psychology of his models.

In 1780, he was appointed academician of the Academy of San Fernando. His career experienced meteoric rise: Deputy Director of Painting in 1785, King’s Painter in 1786, then Court Painter in 1789 under Charles IV. This golden period allowed him to live grandly, as he wrote to his childhood friend Martín Zapater in correspondence that provides precious testimony about his life.

The Artistic Revolution (1793-1799)

In 1793, a severe illness—probably lead poisoning from pigments—left Goya permanently deaf. This ordeal marked a decisive turning point in his art. Freed from the constraints of his official duties, he devoted himself to more personal and audacious works.

He painted a series of fourteen “cabinet” paintings on tin-plate that he qualified as “caprice and invention,” exploring dark themes: madness (Yard with Lunatics), violence (Bandits Attacking Travelers), tragic bullfighting. These works can be considered the beginning of Romantic painting.

In 1799, he published the print series Los Caprichos, 80 etchings of striking modernity that blend social criticism with the oneiric world. Perfectly mastering etching and aquatint techniques, he created images of extraordinary expressive force. The most famous, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, synthesizes his Enlightenment philosophy: when reason sleeps, irrational forces are unleashed.

This period also saw the birth of his pictorial masterpieces: the frescoes of San Antonio de la Florida (1798), with revolutionary impressionist technique, and his most accomplished portraits, notably those of the Duchess of Alba, with whom he allegedly maintained a passionate relationship.

Chronicler of History (1800-1814)

The turn of the century revealed Goya as an uncompromising chronicler of his epoch. In 1800, he painted The Family of Charles IV, a group portrait of striking psychological realism that, according to some, already revealed the mediocrity of the royal family.

He also executed the mysterious Majas: The Nude Maja (1790-1800) and The Clothed Maja (1802-1805), the first realistic nude in Western art that would earn him an Inquisition trial in 1815.

The Spanish War of Independence (1808-1814) inspired Goya’s most poignant works. The Disasters of War (1810-1815), a series of 82 prints, constitutes an implacable indictment against the horrors of war, anticipating modern photojournalism. His two canvases The Second of May and The Third of May (1814) revolutionized history painting by substituting the traditional hero with an anonymous people victimized by blind violence.

The Dark Years (1815-1824)

The absolutist Restoration of Ferdinand VII placed Goya in a delicate situation. His liberal friendships and service under Joseph Bonaparte earned him the regime’s distrust. He took refuge in increasingly personal and somber art.

Between 1819 and 1823, in his country house, the “Quinta del Sordo” (House of the Deaf Man), he painted directly on the walls fourteen works of stupefying modernity: the Black Paintings. Saturn Devouring His Son, Witches’ Sabbath, The Dog bear witness to a pessimistic vision of humanity and a technique of absolute freedom that anticipated Expressionism and even abstract art.

This period also saw the creation of Los Disparates (1815-1824), an enigmatic print series with oneiric and violent visions that pushed exploration of the irrational even further.

French Exile (1824-1828)

In 1824, fearing political repression, Goya exiled himself to Bordeaux where numerous Spanish liberals lived. Far from being an exhausted artist, he continued to innovate, learning lithography with The Bulls of Bordeaux (1824-1825).

His final works, notably The Milkmaid of Bordeaux (1825-1827), reveal a surprising return to color and serenity, anticipating Impressionism. His drawings from Albums G and H testify to a persistently keen eye on the human condition.

Goya died April 16, 1828, in Bordeaux. His remains were repatriated to Spain in 1919 and today rest in the church of San Antonio de la Florida, at the foot of the frescoes he had painted.

Artistic Legacy

Goya’s evolution was exceptional: starting from late Baroque, he traversed Rococo and Neoclassicism to arrive at a profoundly personal style that announced all modern artistic movements. As he himself affirmed, he had “no other masters than Velázquez, Rembrandt, and Nature.”

His influence on modern art is considerable. French Romantics, notably Delacroix, drew inspiration from his example. Manet drew from his psychological realism. Expressionists and Surrealists saw him as a precursor. Picasso himself acknowledged his debt to the Aragonese master.

Goya embodies the passage from ancient to modern art. The first artist to completely free himself from academic conventions, he opened the way to a new conception of painting where expression takes precedence over ideal beauty, where human truth, even when disturbing, becomes art’s central subject.

His multiple œuvre—paintings, prints, drawings—testifies to absolute creative freedom and a modernity that continues to fascinate. Goya remains one of the essential milestones in Western art history, a bridge between the old masters and the artistic revolutions of the 19th and 20th centuries.